May-June 2002

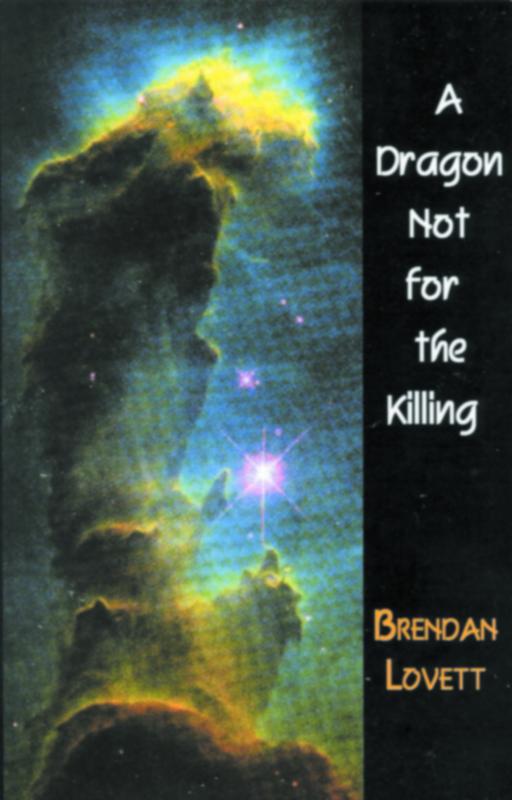

A Dragon Not For The Killing

By Brendan Lovett

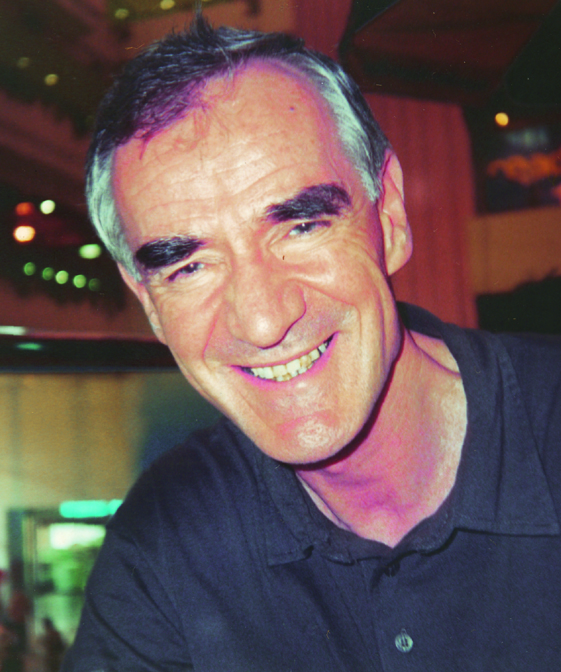

Fr. Brendan Lovett was interviewed by the Far East on his book A dragon not for the killing. Fr. Lovett is one of the leading theologians in Asia and this study on his thoughts on ‘consumerism’ will reward the reader with some very valuable insights. You may have to read it twice carefully, but it is worth it.

Fr. Brendan Lovett was interviewed by the Far East on his book A dragon not for the killing. Fr. Lovett is one of the leading theologians in Asia and this study on his thoughts on ‘consumerism’ will reward the reader with some very valuable insights. You may have to read it twice carefully, but it is worth it.

Q: What are the main issues you address in your most recent book ‘A Dragon not of the Killing?’

A: There is really only one issue unifying the whole book. It is the effort to clarify authentic human development. For over 30 years I have grown in the conviction that the meaning given to development in our times is deeply mistaken. We have mis-defined what is humanly desirable. The prevailing ‘wisdom’ about how to achieve happiness and fulfillment is mistaken.

Q: What leads you to this conclusion?

A: Two things in particular, the impoverishment of so many people in our world and the rapid destruction of our environment. These are consequences of the modern process of development.

Q: You imply that nearly all of us have bought into a mistaken idea of progress.

A: Yes. While the current language of ‘development’ dates from 1949, the underlying trend goes back further. For centuries the Western world has been moving towards making economic value the dominant value, at the expense of a whole range of other essential human values. There is an almost total contradiction between what is promoted by religious value and those of a culture where economic value is consistently given unquestioned priority. Within such a situation, a given religious tradition will have either a radical existence or a miserable one.

Q: One suspects that not too many people see it that way. In the end who decides what is ‘good’?

A: The deeper question, surely, is how we come to decide about any good. While people rightly react against an imposed universalizing morality, it will hardly do to glorify difference as if it were simply arbitrary. That could easily lead to seeing life as a game where you make your own choices but don’t face up to the reality of a world which is dominated by one definite value system. And this system is creating a world where many must live in misery.

Q: Do you believe that what is presented as progress is often in fact impoverishment?

A: Yes. There is no such thing as automatic progress. Economics – or any other social system – should not be allowed to operate as an unquestioned system. It has to be integrated within what cultural process determines as other priorities – its effects on people and environment, for example. Today we have four trillion dollars around the world at electronic speed, “controlled” only by the gambling whims of investors, and effectively determining the life and death of millions of human beings.

Q: When faced with realities like that many good-willed people feel helpless. What can they do?

A: First of all we must believe that we were born to “see through” things, that this is our dignity and right.

Secondly, perhaps, we must believe that we were born to “see things through” and that we do this by commitment to the only thing we have going for us as human beings, the ongoing self-correcting process of learning. When faced with a major, long-term “mistake” we do, of course, find it very disconcerting to put it mildly. What we need most is the courage to inform ourselves about, then to live with the painful knowledge of the harm that is being done until such time as the pain empowers us to discern what steps need to be taken.

Because a totalizing economic system dominates everything, especially the media, people are bombarded morning, noon and night by only one version of what life is meant to be. It is very difficult to find space for alternative thinking. Many people understandably cave in to the myth of “This is the way things are”. We need both compassionate understanding of our predicament and the courage of hope, born of a belief in the life that is in us.

Q: You say that the acceptance, even unconsciously, of the priority of economic values, affects the way we practice our religion. How?

A: If our starting point is “This is the way things are” then our understanding of all of our religious celebrations and symbols will tend to be quietly adapted so as to be compatible with this unchangeable situation. To this extent, the symbols will tend to be emptied of their real meaning. Faith involves accepting responsibility for life in our own time and place and the refusal to take on this responsibility is the death of what religious traditions have meant by faith. Often religious believers who with good reason refuse to allow the importance of the living God to be relativised in their lives are today written off as ‘fundamentalists.’

Q: This is particularly true when political issues are under discussion. There are those who say that what they see as religious arguments have no place in political decisions.

A: All great religious traditions can, in the phrase of Nicholas Lash, be read as “protocols against idolatry”. Religion becomes highly relevant to political or economic social systems that have become idolatrous by being placed beyond the demands of justice.

Recently Samuel Huntington claimed that future wars would be the result of “clashes of civilizations” since the ideological wars are over and there is now only one economic system operative globally. This is the sort of theory that emerges when economics is given absolute priority. To me it seems extraordinarily perverse to see cultural pluralism as the cause of our problems. It serves to mask the real cause of deep tensions in our present world, the manner in which the workings of an uncontrolled economic system is undermining human communities everywhere.

Q: You say culture is the central element. What do you mean?

A: I am not thinking about the sort of things that fascinate tourists. They are the products of culture. In speaking of culture, I refer to the process, the unique activity whereby humans realize themselves in their naming of the world and in deciding for themselves what is humanly worthwhile. Culture is undermined and people as people trivialized when we allow someone else to dictate the meaning of things to us, to tell us, for example, that the meaning of life lies in consuming more and more.

Q: Where does Christianity fit into this world that you describe?

A: If my basic analysis is correct, the answer may well be that it does not! There is no given place for it. We, rather, must create the space for it through living our lives uncontrolled by the fear of death. We must believe in the importance to our world of our struggle for authenticity. The real hope is that people might pay attention to their deepest feelings, feelings like emptiness, and respond to them. Our Christian symbols tell us that we are a ‘remembering’ people. We must resist those who urge us to forget the story of the suffering of others, to dedicate ourselves to self-interest, to become insensitive to the world around us.

Q: A common argument today is that goodness is not linked to being religious.

A: Perhaps that turns on what is meant by “being religious”. The kind of religion that seems much in demand in the West today has been named “pro-religious godlessness” by J.B. Metz. He sees people as still enthralled by religious myths and symbols, yet what these promote is, not happiness, but avoidance. It is as if we are looking for comfort rather than a relationship to Mystery.

Our present sense of the value of the human person did not just fall out of the sky: we are indebted to the Christian tradition for it. It will not survive the elimination of God from our thinking.

The commodification of everything comes to include people. For the commodity market we are all easily replaced. People who cannot see the mystery at the center will find difficulty in sustaining their relationship to the mystery in each other.

Fr. Brendan Lovett lectures in theology in Manila. He has been a lifelong student of the writings of Bernard Lonergan. He is the author of several books.

Because God Is Wise

By Fr Declan McNaughton MSSC

I came from a fairly typical Irish Catholic background and was educated at schools run by nuns, the Christian Brothers as well as a parochial school. When I first became interested in the priesthood in my early teens, it was in my own diocese that I was interested in serving. However, we received the Columban magazine, the Far East, so it was natural that I should begin to read the articles written by Columbans telling about the situations that they were working in. What impressed me was the lack of priests in all of these countries, the plight of the people who were not able to receive the Sacraments regularly and thus was born my missionary vocation.

I came from a fairly typical Irish Catholic background and was educated at schools run by nuns, the Christian Brothers as well as a parochial school. When I first became interested in the priesthood in my early teens, it was in my own diocese that I was interested in serving. However, we received the Columban magazine, the Far East, so it was natural that I should begin to read the articles written by Columbans telling about the situations that they were working in. What impressed me was the lack of priests in all of these countries, the plight of the people who were not able to receive the Sacraments regularly and thus was born my missionary vocation.

Hazy road ahead

I entered the Columban seminary in Ireland, Dalgan Park, in 1966. The Vatican Council had just finished the previous year and, of course, I had no idea what an impact it was going to have on not just the seminary but on the understanding of mission and priesthood. In my first year there, most of the Mass was still in Latin, we wore soutanes all the time, permission to leave the grounds was not readily obtained and times for recreation and study were strictly regulated.

Declining vocations

Happily, all these things changed, but not so happily, the numbers in the seminary dropped dramatically from over 190 in my first year to 40 at my ordination. Vatican II challenged us in the Church to re-examine our understanding of the priesthood and of mission. The old narrow idea of simply saving souls through administration of the Sacraments no longer seemed as relevant as it did before, but no other clear conception of the missionary’s role had been formulated, hence many students left and numbers entering dwindled.

Clear call, clear answer

Although my reasons for wishing to become a priest were originally based on the old model of what he should be, and during that time it was not clear to me what the new model would be, I can say that I have never doubted that God called me to be a priest. This conviction sustained me through the seminary.

I regard this conviction as coming not from any application to study or prayer on my part, but as a gratuitous gift from God, by which sustained my vocation through the years. It was probably a very wise thing for God to do, because He probably knew what would have happened if it had been left up to study and prayer on my part.

Dad, It’s Ok To Cry

By Ma Teresita R. Santiago

Tes Santiago’s mother is an avid supporter of Misyon so Tes has come to love the magazine. Because of the many inspiring stories Misyon has featured, Tes has been dreaming of becoming a missionary herself – and she is still praying about it. Meantime, she wants to share her own story…

Daddy’s Girl

In August 2000, my father was diagnosed with cancer and the doctor advised that he only had six months to live. I had thought then that this was going to be the lowest point of my life. I was so close to Pop. My brothers and sisters always told me I was my father’s pet. This is somehow true because since I was little, wherever Pop was, I always tagged along, giving up everything just to be with him. He was a military man and he had a very strong personality. We looked up to him as a very honorable man, very firm, someone who can never be swayed. He had always taught us honesty, respect for others, hard work, generosity and frugality – these were never hard to learn because we saw these traits in him.

Both in wheelchairs

I made sure that I spent much time looking after him in the hospital. When we brought him home by September, I was his home nurse, administering Insulin shots and attending to his other needs. But as the days went by, Pop continued to lose weight. He was not at all improving like we fervently prayed he would. Their golden wedding anniversary was soon to come and it was my earnest wish that he and Mama would be able to renew their marriage vows. I didn’t give up in begging God to help Pop and allow him to celebrate this special occasion. And when he did, I was never happier. Both in their wheelchairs, my parents renewed their 50th year of being together.

Test of cancer

By March the following year, Pop started losing weight drastically, lost his appetite and was bedridden. He was no longer talking and we were wondering maybe these were his last moments with us. It was Palm Sunday and we were preparing to give communion to Pop. But to our surprise, when we arrived in the hospital, Pop was talking with his eldest granddaughter Molly. Watching him talk after a long time of grimacing in silence, I was warmed all over.

Cry like a man

I greeted hum and showed him the blessed palm which I got that morning Mass. He said it was not a Palm Sunday but a “Pop Sunday” and said that someone will pass away that day. I asked him was he referring to himself, and he just smiled. This was the start of our deep conversation, about our belief in God, death, God’s promise of eternal life. I asked him was he afraid to die and he said no but he felt like he was in an execution chamber and began asking questions: Was he a good man? A good son? A good brother? A good father? I told him, “Yes, you are a good father. You can see that in the seven of us, your sons and daughters.” Then he asked, “Is it okay to cry?” I can’t remember if I had seen him cry before. Maybe because he was a military man and military men are expected to be really tough. I said, “Yes, it is okay to cry.” And he cried.

Brown scapular

While we were talking, I saw the brown scapular he was wearing and held it in my hand. I reminded him of the promise of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel that “Whoever dies wearing the brown scapular shall not suffer eternal fire.” He then recalled one of our out-of-town trips in Vigan when he left his brown scapular in the bathroom. He was so sorry that he never got it back and so Mom gave him another one. Then he remembered Mom and felt sorry for her, for leaving her alone at home. I assured her that when he’s gone, we would take care of Mom the way he took care of her.

Farewell Dad

The last day we heard Pop speak was when his high school friends visited him. He was so full of fun and energy and he talked and laughed a lot. Watching him so alive I couldn’t help but wish for a miracle that Pop wouldn’t die. Not a single day passed without visitors in the hospital. Friends, relatives, officemates, brothers and sisters in the community came to offer support and prayers. It was so comforting to think that Pop was a loved man.

His remaining days were just spent in groaning, sleeping, sometimes shedding of tears. I could see how Pop was suffering because of the grimacing of his face. I reminded him about what Mom said that every time we feel pain, we are sharing in the suffering of Jesus and we can offer that suffering for poor souls in purgatory.

Then on April 25, Pop gave his last smile to Mom – his bestfriend, his partner for 50 years, his classmate since elementary, his companion in times of grief, in times of sickness, in times of need, in happiness and sorrow. Pop left us with a smile on his face and this was more than just enough to comfort us.

Losing someone

Losing someone I love was not the lowest point of my life like I always thought it would be. There is grief, of course. There is a sense of loss, of loneliness, of longing. Once in a while I still break down and cry, realizing how much I miss my Pop. But more than that, I rejoice in the Lord’s assurance of eternal life for those who believe in Him.

Father Joeker

By Fr Joseph Panabang SVD

Which is Which

Trying to welcome a group of elders who came to see me in my hometown during my last vacation I pulled out a bottle which I though was the lambanog whisky given to me by my benefactors in Baguio. Everybody was commenting that the drink was perfect. It was their first time to taste such. The following day, as I was preparing for the Mass, I discovered the bottle I had offered was the Mass wine. It was the bottle nicely covered with red Japanese paper, similar to the cover of the lambanogbottle. What a costly mistake. And no, I did not use the lambanog for the Mass.

Appearances can deceive

My two SVD companions from Indonesia and myself were in Cologne, Germany to see the mighty Gothic Cathedral unparalleled in its imposing arches and majestic beauty. From the Cathedral we stopped at Burger King Restaurant which had a huge bright poster in front with a picture of three big pieces of chicken legs. “Very cheap and yet very big,” we all believed. When our orders came, we were stunned to find out that the chicken legs were as a size of a thumb! Exchanging deadpan looks with my companions, I thought, under that poster they should have put: Warning! Objects in this picture appear bigger than they really are.

Identity Crisis

My puppy, Peace, gets along well with the kittens in the convent. He plays with them, he sleeps with them and even eats with them. One day I came home from work in one of the villages in Ghana and, to my great horror, Peace jumped all over me sounding, “meyaw…meyaw…” You could only imagine the trouble I have had to go to in teaching him how to bark like a dog. After all what would the other dogs think?

Nabisto Ako

In our Renewal Course in Rome back in 2000, my classmates and I attended a Mass. I enjoyed observing the organist who played very well on the Yamaha electronic organ. When time came for Communion he set the electric organ to automatic so it would play away on its own while he went for Communion. I couldn’t resist taking over the organist’s chair as if I was actually playing. Meanwhile the instrument played on. Everyone was surprised to see how proficient I was but when I stood up to go to Communion myself and the organ continued to play on happily, nabisto ang aking palabas.

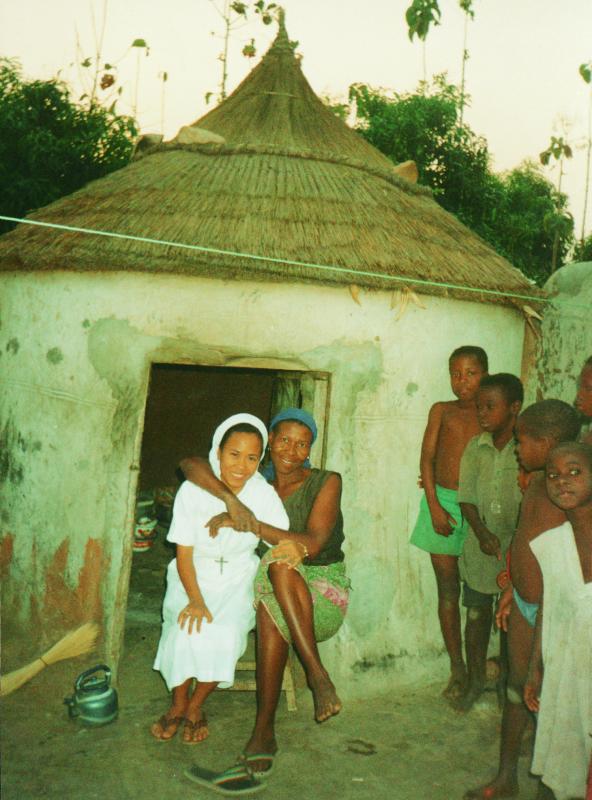

Ghana Won’t Run Out Of Angels

By Sr Rowena S. Cardinoza SSPS

It has been five years since I first came to Ghana. I am assigned here in West GonjaHospital in the accounting department. It is the only hospital in the whole district. The West Gonja District is interestingly the largest district in Ghana, over 130 kms away from the district capital Damongo. As an agency hospital, it is assisted partly by the government.

Floods and plague

As a mission institution the main problem is finance. The beneficiaries of the health services are mainly the poor farmers who struggle every day to get their daily bread and most often the weather is not in their favor. For instance in the last years, some areas of the district were flooded and some experienced plague or locust, which destroyed all the crops. As a result, the harvest was very poor leading to higher prices of food due to shortage of food supply. As a result, many of our patients were unable to pay their bills and these are simply bad debts. For this reason the internally generated funds from the hospital are just too meager to cope with the huge expenditure incurred by the hospital and numerous problems that the hospital is grappling with.

Surviving hospital

It is extremely difficult for the hospital management to provide basic equipment and transportations for patients, drugs and logistics, medical supplies to ensure quality care for the sick and suffering in this particular remote district. Damongo is 700 kms away from Accra, Ghana’s capital. The population is very scattered and there are so called “over sea” areas which are usually cut off by natural barriers (rivers) during the rainy season. The hospital is the only reliable health facility in the area and it is not accessible to all inhabitants because of the natural barriers, poor road network and lack of transportation just to mention a few.

With regards to utility services, it was only in 1998 when we finally had electricity in the hospital. Prior to that, we had a lot of problem with regards to power system, our generators were running 24 hours and at times all were broken down at the same time. Could you imagine the amount of fuel and repairs we had spent?

What keeps me here

These are the difficult things we encounter here everyday. And these are the things that keep me here. Working in this remote area is very interesting and has always been challenging. It is not easy, at times it is draining me but I always feel consoled when I see the hands of God intervening during very difficult times. Sometimes I would think there is no more hope but then all of a sudden, help will come.

God’s delays are not God’s denials

Just recently, the Loretto Sisters Special Needs Funds, based in America, gave the hospital 25 brand new phoenix bicycles distributed to the workers to ease their transportation difficulty. The hospital doctors and nurses also used to have difficulty in going for sick calls because of the poor road network and a broken down vehicle. There is no suitable ambulance. Thanks to Valco, a joint American and Ghanaian company operating in Ghana. They provided us with a brand new four-wheel drive Mitsubishi pick-up in May last year. It is serving as ambulance for the meantime.

With these, I have come to realize that this is not my work for God. This is the work of God. And I believe there will always be laborers to join and help us in this faraway vineyard. Because I know God doesn’t run out of angels to send.

Holy Fools

By Jim Forest

Few taunts are sharper than those that call into question someone’s sanity. Yet there are saints whose acts of witness to the Gospel fly in the face of what most of us regard as sanity. TheRussian Church has a special word for such saints, yurodivi, meaning holy fools or fools for Christ’s sake.

While there is much variety among them, holy fools are in every case ascetic Christians living outside the border of conventional social behavior – people who in most parts of the developed world would be locked away in asylums or ignored until the elements silenced them.

Perhaps there is a sense in which each and every saint, even those who were scholars, would be regarded as insane by many in the modern world because of their devotion to a way of life that was completely senseless apart from the Gospel. Every saint is troubling. Every saint reveals some of our fears and makes us question our fear-driven choices.

‘Unnoticed saint’

In Leo Tolstoy’s memoir of childhood, he recalls Grisha, who sometimes wandered about his parent’s estate and even into the mansion itself. “He gave little icons to those he took a fancy to,” Tolstoy remembered. Among the local gentry, some regarded Grisha as a pure soul whose presence was a blessing, while others dismissed him as a lazy peasant. “I will only say one thing,” Tolstoy’s mother said at table one night, opposing her husband’s view that Grisha should be put in prison. “It is hard to believe that a man, though he is sixty, goes barefoot summer and winter and always under his clothes wears chains weighing seventy pounds, and who has more than once declined a comfortable life…it is hard to believe that such a man does all this merely because he is lazy.”

Grisha represents the rank-and-file of Russia’s yurodivi. Few such men and women will be canonized, but nonetheless they help save those around them. They are reminders of God’s presence.

Basil, the vagabond

The most famous of Russia’s holy fools was St. Basil the Blessed, after whom the Cathedral on Red Square takes its name. In an ancient icon housed in that church, Basil is shown clothed only in his beard and a loin cloth.

The most famous of Russia’s holy fools was St. Basil the Blessed, after whom the Cathedral on Red Square takes its name. In an ancient icon housed in that church, Basil is shown clothed only in his beard and a loin cloth.

It is hard to find the actual man beneath the thicket of tales and legends that grew up around his memory, but according to tradition Basil was clairvoyant from an early age. Thus, while a cobbler’s apprentice, he both laughed and wept when a certain merchant ordered a pair of boots, for Basil saw that the man would be wearing a coffin before his new boots were ready. We can imagine that the merchant was not amused at the boy’s behavior. Soon after – perhaps having been fired by the cobbler – Basil became a vagrant. Dressing as if for the Garden of Eden, Basil’s survival of many bitter Russian winters must be reckoned among the miracle associated with his life.

Stripped off

A naked man wandering the streets – it isn’t surprising that he became famous in the capital city. Especially for the wealthy, he was an annoyance. In the eyes of some, he was a troublemaker. There are tales of him destroying the merchandise of dishonest tradesmen at the market on Red Square.

Vain fasting

Basil was one of the few who dared warn Ivan the Terrible that his violent deeds were dooming him to hell. According to one story during the Great Fast, Basil presented the tsar with a slab of beef, telling him that there was a reason in his case not to eat meat. “Why abstain from meat when you murder men?” Basil asked. Ivan, whose irritated glance was a death sentence to others, is said to have lived in dread of Basil and would allow no harm to be done to him.

Soon a saint

Basil was so revered by Muscovites that when he died, his thin body was buried, not in a pauper’s grave on the city’s edge, but next to the newly erected Cathedral of the Protection of the Mother of God. The people began to call the church St. Basil’s, for to got there meant to pray at Basil’s grave. Not many years passed before Basil was formally canonized by the Russian Church.

St. Francis of Assisi

While such saints are chiefly associated with Orthodox Christianity, the Roman Catholic Church also has its holy fools. Perhaps St. Francis of Assisi is chief among them. Think of him stripping off his clothes and standing naked before the bishop in Assisi’s main square, or preaching to birds, or taming a wolf, or – during the Crusades – walking unarmed across the Egyptian desert into the Sultan’s camp. What at first may seem like charming scenes, when placed on the rough surface of actual life, become mad moments indeed.

In His Image

It is the special vocation of holy fools to live out in a rough, literal breathtaking way the “hard teachings” of Jesus. Like the Son of Man, they have no place to lay their heads, and live without money in their pockets. While never harming anyone, they raise their voices against those who lie and cheat and do violence to others, but at the same time they are always ready to embrace them. For them, no one, absolutely no one, is unimportant. Their dramatic gestures, however shocking, always have to do with revealing the person of Christ and his mercy.

For most people, clothing serves as a message of how high they have risen and how secure – or insecure – they are. Holy fools wear the wrong clothes, or rags, or perhaps nothing at all. This is a witness that they have nothing to lose. There is nothing to cling to and nothing for anyone to steal. “The Fool for Christ,” says Bishop Kallistos of Diokleia,” has no possessions, no family, no position, and so to speak with a prophetic boldness. He cannot be exploited, for he has no ambition; and he fears God alone.” The voluntary destitution and absolute vulnerability of the holy fool challenges us with our locks and keys, and schemes to outwit destitution, suffering and death.

Holy fools may be people of lesser intelligence, or brilliance. In the latter case such a follower of Christ may have found his or her path to foolishness as a way of overcoming pride and a need for recognition of intellectual gifts or spiritual attainments. The scholar of Russian spirituality, George Fedotov, points out that for all who seek mystical heights by following the traditional path of rigorous self-denial, there is always the problem of vainglory, “a great danger for monastic asceticism”. For such people a feigned madness, provoking from many others contempt or vilification, saves them from something worse, being honored.

Holy fools pose the question: are we keeping heaven at a distance by clinging to the good regard of others, prudence, and what those around us regard as sanity? The holy fools shout out their mad words and deeds that to seek God is not necessarily the same thing as to seek sanity. We need to think long and hard about sanity, a word most of us cling to with a steel grip. Does fear of being regarded by others as insane confine me in a cage of “responsible” behavior that limits my freedom and cripples my ability to love? And is it in fact such a wonderful thing to be regarded as sane? Adolph Eichmann, the chief administrator of the Holocaust, was declared “quite sane” by the psychiatrists who examined him before his trial.

Holy fools challenge an understanding of Christianity that gives the intellectually gifted people a head start not only in economic efforts but spiritual life. But the Gospel and sacramental life aren’t just for smart people. At the Last Judgment we will not be asked how clever we were but how merciful.

I Crossed The Bridge And I Got There…

By Sr Ma. Luisa Tomaro OND

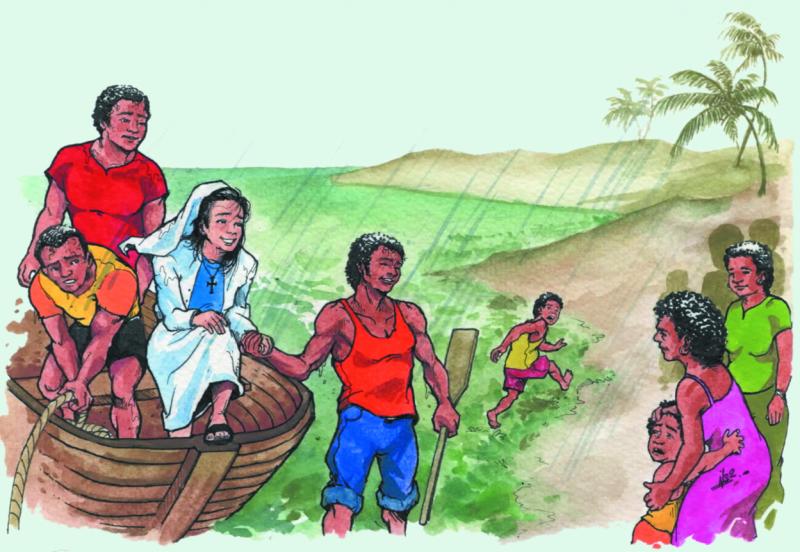

Three years ago, Sr. Luisa arrived in the tropical jungles of Papua New Guinea. She is presently handling family life and catechetical ministry in the parish of Daru. One of their regular activities is ‘patrolling’ – they go from village to village preparing the people for Baptism, Confession, First Communion or Marriage. Here she tells how she has come to cross the bridge of ethnic differences.

In one of our patrol schedules, my four catechist companions and I had to travel by water because the village we were visiting was quite far. There were four of us and I was the only female. We left at 10:30 am, riding on a dinghy. What a terrible trip we had. Ten minutes after leaving Daru, a heavy rain poured. I was frightened because I did not know how to swim. The most I could do was to pray that the dinghy would not sink. The rain soaked us. It was very cold and it lasted for an agonizing four hours.

Culture shock

We reached the village at 2:30 pm. I was astonished because the village leaders placed all of us in one mud hut. Needless to say, it was hard for me because there was no room for changing clothes, no comfort room, no bathroom. I had to sleep next to my three male companions. The people have no regular meals, too. They were not even offering food to us. At night-time I could not sleep well because of back pains. The floor was not flat and had holes in it.

Color fright

The following day, I roamed around and visited the families. At first, children were crying and running away when they saw me. Later I found out that they were afraid of my strange straight hair and my unnatural fair complexion. They thought I was a witch from the middle of the sea.

This was one of the difficulties in trying to reach out to them. But I always believed in my heart that no matter what our differences were – in language, color, beliefs and traditions, we would always come together in the end, would cross the cultural bridge which divides us.

First impression don’t last

Day after day, I felt more at home with them, talking and eating with them, learning their language, their life. I discovered that they are also warm and friendly people. And I am sure they discovered the same about me. We stayed there for ten days. We gave lessons and briefings for Sacraments and for the last three days our parish priest came and administered sacraments of Baptism, First Confession, First Communion and Marriage.

Dinghy rides and more

This was not my last patrol. There are still plenty of patrol schedules to come, many dinghy rides. Nevertheless, I still want to go because nothing compares to this feeling of being a part of somebody else’s life, discovering what life is in the other side of the world, learning about other people’s beliefs and traditions and most of all, hearing their own story.

And then, along the way, I would understand why God has made people different from one another.

If There Was Hell…I Was Already There

By Marco Mura

Four years ago to this very day I was holed up in a dark motel room that the roaches had claimed for their own. This sort of environment was nothing new to me. I had walked away from a beautiful wife, two beautiful children, a beautiful home, a job, friends – everything. I had traded it all in for a bag of dope and a needle. I no longer believed in God or worshiped him. Instead I worshiped the heroin and the needle that delivered it. In reality what they delivered was a close brush with death and the prison cell I now call home – my only home, for there is no other.I never knew my father, who was Irish. My stepfather was Italian and my mother was Greek, so I learned the traditions of the Orthodox faith. But our primary religion was Catholic. I went to St. Jospeh’s, a Catholic grade school in New York City. I loved it there because the nuns and everyone else were very kind to me. They knew my home was a painful place. During gym they could see the bruises and cigarette burns on my arms and legs. I carry scars from the burns to this day.

Four years ago to this very day I was holed up in a dark motel room that the roaches had claimed for their own. This sort of environment was nothing new to me. I had walked away from a beautiful wife, two beautiful children, a beautiful home, a job, friends – everything. I had traded it all in for a bag of dope and a needle. I no longer believed in God or worshiped him. Instead I worshiped the heroin and the needle that delivered it. In reality what they delivered was a close brush with death and the prison cell I now call home – my only home, for there is no other.I never knew my father, who was Irish. My stepfather was Italian and my mother was Greek, so I learned the traditions of the Orthodox faith. But our primary religion was Catholic. I went to St. Jospeh’s, a Catholic grade school in New York City. I loved it there because the nuns and everyone else were very kind to me. They knew my home was a painful place. During gym they could see the bruises and cigarette burns on my arms and legs. I carry scars from the burns to this day.

From one place to another

My parents could not keep it together. We moved all over New York City in the 1960s and ‘70s, rarely staying in one place more than a year and never unpacking all our things because we knew the next eviction was right around the corner. I could never keep any friends and never brought anyone home for fear of the shame and embarrassment. That was my life – poverty, occasional homelessness when we slept in our car or in shelters, and the beatings and cigarette burns from my stepfather.

Stitches

I remember going to the hospital emergency room after a beating because I needed stitches. I had to lie to the doctor about what had happened because if I didn’t I would be beaten again, and my mom would tell me that if I told the truth my brothers and I would be taken away and split up and put in orphanages. I kept my mouth shut because I couldn’t stand to be separated from my brothers. There were times when we kids were taken away and put in foster care, which was an emotional vacation for us. It meant we didn’t have to worry every waking moment about being beaten, and we could relax for a while. I took most of the beatings. Sometimes when my stepfather was drunk and out of control I would climb on top of my brothers to shield them. My brothers were my life, and I loved them so much. They were all I had. And now they are no longer in my life because of the path I chose – drugs, dirty money, living on the edge, tempting death in all I did.

I remember as a child praying to God in tears for help. Still the beatings and cigarette burns went on until I got big enough to stop them. I believed in God—always!—but could not understand why he would not help me.

My teen and early adult years were filled with trouble – drugs, loss, lies and loneliness. I got married and we had two children. As a child I had promised God one thing: When I grew up, I would never beat or abuse my own wife and kids. I am grateful I kept that promise. But in the end I hurt them anyway. I woke up one morning and just walked away and never went back. I couldn’t see any other way. I was an embarrassment to them. I couldn’t maintain any stability. I truly believed they would be better off without me in their lives.

Heroin

I drifted around, desperate for heroin or any other drug I could get. I became sick and took drugs to make the sickness go away. I broke the law to supply my habit. Eventually it wasn’t even a matter of getting high – I needed drugs just to function. I was deceitful, evil at times, with no regard for human life or people’s feelings. I found myself going to places no sane human being would go for any reason. I saw dead bodies on the floors of crack houses, left there as though they were garbage. I was lost – void of soul and spirit in a dark world – by the time I found myself in that bitter motel room alone with the vices of my desolation.

As I sat on the bed, I had in front of me several bags of heroin, a needle, a bottle full of pills and a six-pack of beer. After the fourth or fifth beer, I noticed a Bible on the nightstand. As I looked at it I became furious. I had come to believe that everything in the Bible, every word was a lie. There was no such person as an all-powerful, loving, compassionate God.

Where was God

I thought to myself, where was God when I was being beaten and burned and degraded and told time and time again that my birth was a mistake, that my parents had tried to give me away but no one would take me? Where was he when I accidentally spilled a glass of milk, and some of it landed on my stepfather’s shoes and that night I was not allowed to eat at the table, and my food was given to me in the dog’s bowl? Where was God when I got down on my knees in pain, pleading for help, crying that I couldn’t take it anymore?

As I sat there in the motel room, I tore out the pages of the Bible, crumpled them, and threw them on the floor. Maybe the roaches will have better luck with the Bible than I have, I thought. I cried harder, cursing God and saying, “It was all a lie!” – all those times as a child, praying to a God who never existed. I felt so stupid. When I had torn out most of the pages I threw the rest of the Bible against the wall, and the tears came more freely.

In my heart, mind, and soul I had come to the end. I couldn’t take the loneliness and emptiness anymore. I was physically sick from years of drug abuse and alcoholism. I was emotionally sick of being ill all the time, chasing the heroin high, stealing whatever I could, selling my blood, my soul, my life to support my habit. Begging for change on the streets, sleeping in a box in some alley, eating out of trash bins when I decided to eat at all (which for a junkie is not often). When I looked in the mirror I could see my body had wasted away. At six feet, four inches tall I had gone from 240 pounds to 170 pounds. My eyes were lifeless and sunken.

I was sick, lost, lonely, hopeless, on the run from the police. Death seemed the only choice, a welcome end to the misery. As far as I was concerned I was dead already, and, if there was hell, I was already there.

In a cold, stony voice I said out loud, “If you are God, if you are for real, then I won’t die from what I am about to do. If I am worth something in this life, then you will save me. Then and only then will I believe.”

If you are God, save me

I loaded up the needle – enough to kill a horse – took three or four Percocet pills, finished my last half bottle of beer, and took a drag of cigarette. I held the needle in front of me, just looking at it, thinking, Is there any reason I should live? None that I could think of. My tears flowed again. The needle found a vein, one of the few that hadn’t closed down. “Please,” I said, “if you are God, forgive me for what I am doing.” The last thing I remember was putting the needle and the pills on the nightstand and just floating away.

I awoke feeling worse than I had ever had in my life. I was nauseous, my head was pounding, and I was having trouble breathing. I opened my eyes and realized I wasn’t in the motel room. Tubes and wires were connected to my body. I could see on a monitor that my heart was steady but not strong. An I.V. drip was in my arm. My clothes were gone, and I was wearing a hospital gown. My eyesight was fuzzy but slowly coming into focus.

The Awakening

“Welcome back, Mr. Mura.” A nurse had walked in with a smile on her face. “We almost lost you there for a while, but by some miracle you held on. I guess it wasn’t your time to go. The doctor will be in to see you shortly.” She must have seen the questioning in my face. “He’s the one who worked on you when the ambulance brought you in.”

Seconds later the doctor came in. “Well, well,” he said. “We thought we’d lost you. But you are a fighter – you wouldn’t give up. We tested your blood and found that the level of heroin was higher than worst-case scenario. But I’m sure you know that, don’t you? You get some rest now. I’ll come back later.”

After he left the room, a series of thoughts ran through my brain. How did I survive? Who found me? Nobody knew I was there except the motel clerk. No one could survive what I had shot into my veins unless he was found I a hurry. The police must know – more than likely they’re here at the hospital. Then I remembered my challenge: “If you are God, then you will save me.”

After he left the room, a series of thoughts ran through my brain. How did I survive? Who found me? Nobody knew I was there except the motel clerk. No one could survive what I had shot into my veins unless he was found I a hurry. The police must know – more than likely they’re here at the hospital. Then I remembered my challenge: “If you are God, then you will save me.”

Moments later a priest entered the room. He had a serious look on his face. “How are you feeling?” he asked. “Not so hot,” I said. “I don’t really understand what’s going on or how I got here or who found me.” My eyes teared up. “I shouldn’t be here. I was supposed to die.”

“You are a very lucky man,” said the priest. “I was called to your bedside to administer last rites because it appeared you weren’t going to make it.” He looked at me keenly, then said, “Do you believe in God, Mr. Mura? Because there is no question in my mind that God had a hand in this miracle. It wasn’t your time to go.” He told me the police were at the hospital wanting to talk to me, and one of them had given him a brief rundown of what had happened.

“The point of interest for me,” he said, “was that they found most of the pages torn out of a Bible and thrown all over the floor.”

Where was God?

I said to him, “Where was God when I needed him as a child, when I was being degraded and treated like an animal – where was he, and why did he wait until now to do something for me?” I told him of the challenge I made to God right before I shot up. “I said, ‘If you really are God and you really do exist, then save my life and I will give my life, heart, and soul to you.”

“Well, I guess you got what you were looking for. It is clear to me he did answer you and that he has a plan for you. Now do you believe?”

Imprisoned

Eventually I was sent to prison on drug charges (a seven-and-a-half to fifteen-year sentence), but it turned out to be the best thing that could have happened to me. The four years I have been here have given my brain and body a chance to heal and given me a chance to heal and given me a chance to find myself and be honest with others, God, and myself.

It took a couple of years to really accept God’s truth and his plan for all of us who believe and have strong faith. I began to pray and study the Bible front to back, over and over. I began to go to the Catholic chapel services at the prison. My faith has been restored to what it was when I was a child, before I had withdrawn into myself from the pain of the world.

Days are like years here in prison. I pray for help and strength to make it through each day. I no longer exist, it seems, in the world beyond these walls. Life has gone on; time has passed without me. I have missed all those precious moments with my children that happen only once in a lifetime and can never be recaptured.

Master’s Degree

I have earned a master’s degree and a Ph.D. through the accelerated correspondence programs offered by the prison. I am in the process of finishing my second book and continue to do my portrait artwork, which I donate to public libraries, schools, and galleries throughout New Hampshireand Massachusetts. Writing and art are more therapeutic than anything else and help pass the time. That’s half the battle in prison – finding something to pass the time, day after day.

Only two years to go, and I will be paroled and pick up the pieces of my life. My heart tells me I should work with addicts and alcoholics like myself to spare them from the hell that I lived (as did my family and loved ones).

In ancient shadows

and twilights where

childhood had strayed

the world’s great sorrows

were born and its heroes

were made

in the lost childhood of Judas

Christ was betrayed.

– AE (the pen name of the Irish poet, George Russell)

I’ll Meet You At Mariamabad

By Seamus O’Leary

Mariamabad is the place to go if you want to meet Catholics in Pakistan. Seamus O’Leary, a Columban lay missionary, took part in the annual pilgrimage to its famous Shrine of Our Lady last year. It was an interesting mix of faith, devotion, fun and business.

Mariamabad is the place to go if you want to meet Catholics in Pakistan. Seamus O’Leary, a Columban lay missionary, took part in the annual pilgrimage to its famous Shrine of Our Lady last year. It was an interesting mix of faith, devotion, fun and business.

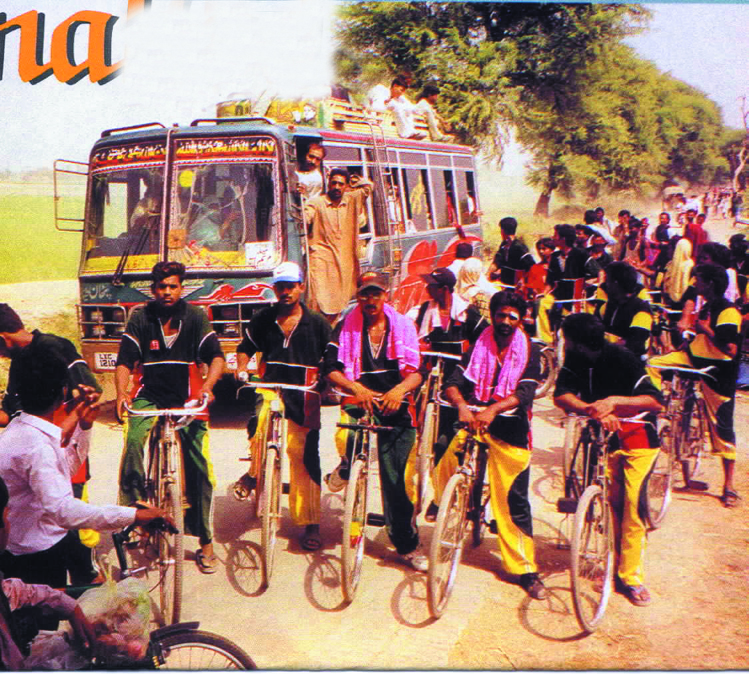

The annual pilgrimage to the Marian Shrine in Mariamabad in Pakistan took place last year from 10thto the 12th of September. It is about 100 kms from the city of Labore. Several people from there walk or cycle to the shrine for this occasion. Many others do so from even further afield. It takes five days of strong cycling, in scorching late-summer heat, to make it from Karachi. Anyway I opted for the cycle from Shadbagh with a group of young men I had gotten to know over the previous months.

Cycling Pilgrims

It certainly was a memorable cross-cultural experience. Fortunately, from the point of view of heat exposure, we cycled during the cool of the night. Unfortunately that meant that vision was negligible. What bicycle lamp? Along the way we mingled with dozens of other groups of cycling pilgrims. In fact at one stage the mingling was a little too tight and a sudden change in road surface sent skin and metal flying in all directions. At a later stage someone else went slap bang into the back of a parked but unlit lorry. However most of us arrived safely few hours after sunrise as, several miles back, pilgrims on foot arose to face the final leg of their journey.

Bold expression of faith

The event in Mariamabad itself was as much a festival of everything imaginable as it was a gathering in honour of Our Lady. Among the thousands who flocked there during the three days did seem to be a real desire of many to assert their identity as Christians. As we cycled through towns such as Sheikhapura the previous night I sensed a curious uncertainty among some local Muslims as they watched droves of pilgrims openly proclaiming the fact that they were Christians in this Muslim society. But having said that, the atmosphere of the festival itself seemed to be, more than anything else, a celebration of the Punjabi culture. Combined with this was the invention of an infinite variety of ways of furnishing someone else with the few rupees one might have. It would be hard to capture the atmosphere of the festival in words.

Peace in Noise

A dominant feature was noise. It was everywhere and greatly increased by countless drummers who were willing, for a few rupees, to beat out the loudest and fastest local rhythm. This was for the benefit of any two of the lads who might feel like competing in a dance to impress the countless onlookers. When I was pushed into the middle at one stage the number of onlookers multiplied considerably. It took me most of the first day there to get used to being stared at as a whiter than white object of curiosity. The young people with me tried to explain that people were just happy to see a foreigner sharing in their culture and festivities. A pinch of salt might be required with that explanation. But I’m sure no one was more happy to see me than whoever it was who relieved me of my sunglasses and romal (head scarf) later that night as some of us tried to catch some sleep amid the ceaseless noise and festivities of the rest. One thing that amazes me about local people here is their ability to switch off from the surrounding noise. Whether this is due to the simple necessity of being able to filter the impact of the world around them or to some other kind of depth and self-presence, I’m not yet sure.

My memories of the festival are of an occasion that was boisterous and lively. Alongside the religious activities there was the variety of sideshows. There were dancing and weight lifting competitions, a mobile zoo and amusements such as the Big Wheel. There were the stalls of traders, stalls selling religious items and stalls selling food. There were the hours of queuing to visit the shrine to offer gifts or flowers to decorate the statue of Our Lady. There were the huge pots of rice which could be bought in honour of Our Lady and then offered to anyone and everyone or to the fastest and the fittest to be more precise! Their place was full with whole families getting on with daily living and with youth seeking every possible attraction. There was hospitality to the point of embarrassment, fervent prayer, a flow of people coming and going by every means, a constant rhythm of life. Beneath it all lay the desire to celebrate and a longing to be recognized.

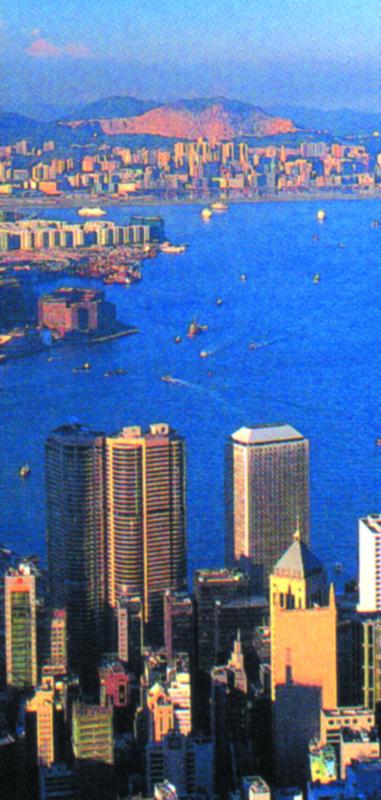

Made In Hong Kong

Over 120,000 Filipinos work in Hong Kong. Before the British left in 1997 there were many European officials who needed nannies and household help and were willing to pay good wages and give good conditions. That has changed now that Hong Kong has reverted to China. Life has become harder but that message has not got back to the Philippines. Sr. Leticia Bartolome, ICM who has worked there for years sends a letter to a friend and tries to change her mind about coming to Hong Kong.

Over 120,000 Filipinos work in Hong Kong. Before the British left in 1997 there were many European officials who needed nannies and household help and were willing to pay good wages and give good conditions. That has changed now that Hong Kong has reverted to China. Life has become harder but that message has not got back to the Philippines. Sr. Leticia Bartolome, ICM who has worked there for years sends a letter to a friend and tries to change her mind about coming to Hong Kong.

We would like to thank Sr. Leticia for accommodating our request to print her name despite her original request to withhold it. We salute her for this brave article.

Dear Eva,

Peace to you and all your loved ones! Thank you for writing and for the trust that you gave me in sharing your hopes and aspirations for the future. But I am really very sorry to disappoint you, in the same way that I have disappointed so many others who have written me for help to find jobs for them here in Hong Kong.

I have been in Hong Kong for the past 28 years and I know the truth regarding the life of the domestic helpers here. They will never tell everything to their loved ones in the Philippines and so those who believe them think that Hong Kong is a “paradise” in many ways.

I personally know many young women who thought that their financial problems at home could be solved by coming over here, only to discover that this problem multiplies into different problems once they are here. And these problems are often so difficult to solve.

The rate of unemployment here continues to rise and the domestic helpers are no longer wanted as before. The women who used to work in the factories here are now working as part-time domestic helpers. There are also women from Mainland China who are also searching for their own future here. So you see, there is a lot of competition now. And do not think of having Western employers here because many of them have also gone home to their own countries. So please be contented with the little that we have in our country and be grateful to God that we have so many values which can never be exchanged with the dollar. Do not look for greener pastures here, but try to look for the opportunities over there.

I see that your children are still young and that your husband has work. Why don’t you give them your time, be with them and guide them, instead of doing this for other people’s children in a foreign land. You will see the blessings of this decision in the future.

Thank you for enclosing some pictures in your letter. Such beautiful smile that greeted me when I opened it. Let that smile bring sunshine over there, among your family, friends and anyone who comes across your path. I have nothing that I can still offer to help you, but be assured that you are included in my prayers. God bless.

Yours sincerely,

Sr. Leticia Bartolome, ICM

Mission Brought Me Home

By Christine Ortaliz

Columban lay missionary Christine Ortaliz shares with us the challenge of adjusting to a new culture. We see something of the marvelous benefits of living for a period in a cross-cultural situation. It was during her stay in Taiwan that she finally came to grips with her own identity.

I came to Taiwan as a lay missionary in March 2000. Right now, I continue to study language and work for the migrant ministry at the Hope Worker’s Center in Taiwan. If you asked me one year ago if I would choose to work at the Center, I would have politely smiled and said “maybe”. But inside I would have been thinking, “No! That’s out of the question!”

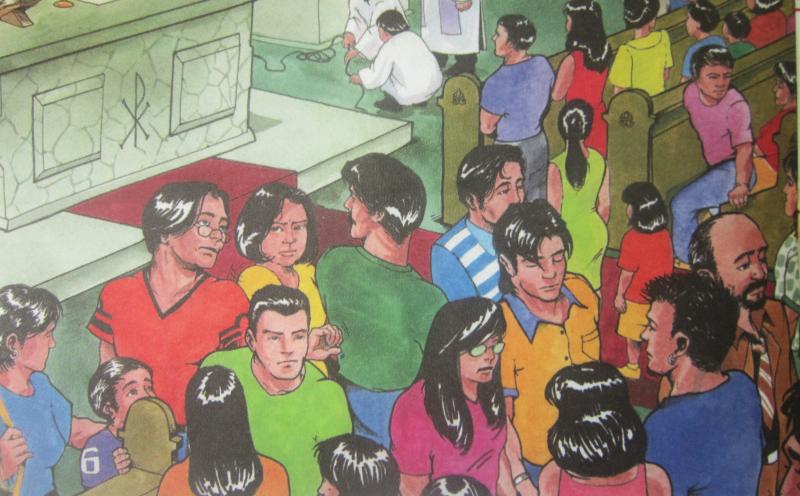

Just a face in the crowd

When I first arrived in Taiwan, I started to attend the English Mass at the Hsinchu Cathedral in Chungli. The church was packed with hundreds of Filipinos sitting shoulder to shoulder, everyone sticking to each other with the help of Taiwan’s muggy weather. I felt a bit claustrophobic, almost like I was suffocating. I also grew a bit depressed because I looked just like everybody else: short stature and black hair. Even if I came to Mass 15 minutes early, I could barely make it through the main doors. “Excuse me, please,” I would say as I would weave my way through. Immediately people would stare at me and whisper to each other in Tagalog. That annoyed me. I cringed at the sound of Tagalog. I couldn’t understand any of it. Yet most of the songs were in Tagalog, not to mention everyone around me spoke it. I would feel frustrated and angry.

I felt like a sardine

Leaving the church would take a long time, too. Over 1,000 Filipinos would exit the church while about the same number would enter at the same time. I felt like one of those sardines – no space, no air, nowhere to move. Instead of finding peace, hope and renewal at the Sunday Masses, I found myself stressed and drained.

I then realized that I had many prejudices against the Filipinos and looked down on them.

I never knew where I came

Discovering my prejudices shocked me. I felt embarrassed, confused and ashamed. How could I possibly feel this way? My parents are both Filipino themselves! Furthermore, how could I be a missionary while holding all these prejudices?

Who am I?

My prejudices stemmed from my ignorance of my parents’ culture and my negative childhood experiences with it. My parents were the first generation to go to the States, so I was born and raised there. They never taught me to speak their dialect – Ilonggo, nor did they teach me to speak Tagalog. They never shared much about their own cultures and traditions. I don’t even recall hearing many stories about their childhood in the Philippines or their past.

As a child I had visited the Philippines once to visit my grandparents and relatives. I have never seen them since. I just remember I didn’t like the hot and sticky weather. So am I Filipino? Am I American? Am I Filipino-American? These questions are always up for debate not just among the Filipinos here, but among people I encounter in Taiwan.

Greater Understanding

Last year my ministry at the Hsinchu Cathedral provided an opportunity to meet many of the Filipino migrant workers and make a small group of friends. Little by little I began to understand that we had more similarities than just “Filipino” blood. Just like I did, they left everything to come to Taiwan – their country, their families and their friends. But they brought with them faith and hope, which we all shared when we worshiped every Sunday. Now I see them as my sisters and brothers. With a growing understanding, I slowly began to find that peace and renewal that I needed at the Mass.

Sunday lessons

Every Sunday for the past three months I have gone to the Hope Worker’s Center. When I can, I shadow some of the social workers to learn more about the different cases they are working on. I have held a few seminars and helped out at the Masses. I am not only learning about the situation of migrant workers in Taiwan and in Asia, I am also learning about the different cultures of the Indonesians, Thais, Filipinos and Vietnamese.

My time in Taiwan has challenged me in unexpected ways. When I learn more about the Filipino culture, I am also learning more about things my parents said and did that never made sense to me. They were Filipinos struggling to raise children in a culture different from their own – the American culture. I never thought my experience here would teach me about my own family’s history and the Filipino culture. These challenges and confrontations I face are not easy. But I believe I am slowly learning to love as Jesus loved – beyond all boundaries and conditions. This includes race and ethnicity.

What Mission is

For me, mission is a journey. Mission is healing. Mission is molding. Mission is freedom. Mission is bringing people together. Mission is discovering who I am. Will I ever be able to have to match the love Jesus had, enough to lay down my life for others no matter who they are? I have the hope that in the end, we all will be like Jesus (1 John 4:7) and love as He loved. Remembering this gives me strength and confidence.

Home to myself

Now when I hear the sound of Tagalog, I get a warm feeling. When we sing the Lord’s Prayer in Tagalog during Mass, I smile and take a brief moment to honor my parents, all relatives, ancestors and the Filipino brothers and sisters around me. I am happy, remembering that all the Filipinos are a part of me, a part of who I am.

Remembering Pinatubo

By Fr Frank O’Kelly MSSC

More than ten years have passed since the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo but for me the memory of that terrible day is still very vivid.

More than ten years have passed since the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo but for me the memory of that terrible day is still very vivid.

On Philippine Independence Day, Wednesday, June 12, 1991 I attended an ecumenical service in the town plaza of Cabangan. At around nine in the morning I returned home to write a letter to the former parish priest, Fr Malcolm Sherrard who had been assigned home to New Zealand.

Ash fall

Suddenly I heard shouting outside. I rushed down the stairs, “See, Father, the sky!” I looked up and saw what seemed to be a gigantic spaceship filled with magnificent colors. I heard rumbling. It grew stronger and stronger and darkness began to descend. Frightened, we hurried home as ash began to fall. I went into my house and closed the windows as the rising wind was beginning to blow the ash inside. Soon total darkness fell. What I remember then was the awful silence, no barking of dogs or crowing of cocks, no noise outside, just an eerie silence. Even the ants had disappeared from the floor. The darkness lasted two hours. Then the rumbling stopped and light began to break. Suddenly it was daylight again. Outside everything looked so beautiful, covered with ash that was so white and bright. Radio announcements told us more eruptions were imminent.

On Saturday, June 15, I went to celebrate 6:00 am Mass with the Benedictine Sisters who lived near the coast of the South China Sea. It was a dark morning and a typhoon was approaching. After I finished Mass a rain that looked like heavy soot began to fall. It was getting darker and I decided to go home immediately.

Journal of Fear

At 8:30 am shortly after I arrived home total darkness descended and the awful sequence of events began — thunder, lightning, earthquakes. The radio had gone silent. I huddled in my chair and tried to read by candlelight. But all I could feel and hear was the awful constant roar. Alone and terrified I went to my bedroom to lie down. Suddenly the windows were smashed in. I ran out to the living room and lay under the heavy oak table trembling and waiting for the avalanche of ash and rocks to destroy the house. After half an hour I emerged from under the table. It was then, and out of fear that I was going to die, that I began to write an hour-by-hour diary of events.

Face to face with death

I will never forget that day that seemed to stretch on and on. I went into the pare room and lay under the bed but the movement of the floor, constantly shaken by the earthquakes, was too great. So I crawled out and lay on the bed. I covered my face with a pillow so that when death came people might be able to identify me. I waited and prayed – a constant prayer of fear. Finally, totally exhausted by terror I fell asleep. It was about 9:00 pm.

I was tossed out of the bed by an earthquake by 4:00 am. The first thing that struck me was the brightness of the room. Opening the windows I saw the whole area covered in volcanic ash. It seemed as if the town had been hit by a tremendous snowstorm.

The fury of lahar

The church, the school, homes and buildings were destroyed. Trees had been bent and twisted by the fury of the eruption. In the weeks following a further tragedy was to befall the people. The heavy monsoon rains from June to October swept the volcanic debris down into the fertile plains of Tarlac and Pampanga. Since the nearest sea was Manila Bay a few hundred miles away the rivers became clogged with volcanic debris and then volcanic ash (lahar) swept across sugarcane fields and rice land, turning them into a white desert. People who had enjoyed a comfortable life were reduced to poverty. Today, much of that land remains unclaimed.

The province of Zambales where Cabangan is located is situated fared a bit better since it is a narrow strip of land hemmed in by the Zambales mountains and the South China Sea. Most of the volcanic debris was carried to the sea a short distance away.

Bayanihan Spirit

When I saw the destruction on that morning of June 15, I asked myself, “God, what will I do?” The response began to come immediately from the Filipino people. They came from all over Luzon – ordinary people, students, doctors and nurses, bishops, priests and sisters. I will not easily forget their love and concern for their fellow countrymen and women. Week after week they came bringing medicine, food, spades, wheelbarrows and seeds. It took tremendous courage to travel in those days because one did not know if there would be another great eruption. Rumor fed on rumor and this generated fear and panic. And still these wonderful people came bringing not only needed materials but also hope, and that special quality of the Filipinos, the “bayanihan spirit” of coming together to help one another. And gradually people began to reshape their lives.

Because they are determined

It was terribly hard for them. Trying to till land covered by a blanket of ash was agonizing. But they did it and today most of the rice lands are fertile again. However the farmers tell me that they get only a third of what they used to harvest in the past. One can only admire the resilience, courage and determination of these people. The cost to the people and the country was enormous. At the beginning there was the loss of life, property and source of livelihood. Work goes on continuously to dredge the rivers. Massive dykes had to be built to control the flow of lahar during the rainy season. Again and again bridges and roads have to be repaired.

The eruption of Mount Pinatubo was described as an ecological disaster. Looking at the land covered in volcanic ash and debris I might be tempted to agree that the disaster was absolute. But perhaps earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are necessary or otherwise planet earth might die.

A rich land

Yes, I have seen the destruction and desolation caused by the volcano but I have also seen vegetation and plant life appear on hills and mountains that lay waste and barren before the eruption. Coral reefs that had been destroyed by dynamite fishing are beginning to come alive again through the massive fall of volcanic ash on the South China Sea.

When the Spaniards saw the central plain of Zambales in the 16th century they were amazed at two things – absence of people and the richness of the land and the forests. There had been an eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the 12th century. Maybe it was then the people living close to the mountain fled. Over the centuries, life with a greater richness and fertility was restored to a land that seemed to be destined to be forever a desert.

While there is life

Someone asked me once if there was one memory in particular that would always remain from this chapter of my life. Yes, there is.

A few weeks after the eruption I went to one of the villages close to Mount Pinatubo. The land had been devastated, the rice fields and fruit trees destroyed. Many of their houses and the church were flattened. It was near annual fiesta time. “Will we have our fiesta Mass this year?” I asked, looking around at the desolation. “Oh! Yes, Father, we want to offer a Mass of thanksgiving.” I thought of the suffering, the demolished homes and fruit trees and said, “Why do you wish to offer a Mass of thanksgiving?” “Ah! Father,” they replied, “we are alive.”

Salamat sa Far East

Tears Were Shed In Candoni

By Fr Niall O’Brien MSSC

When I came first to the island of Negros, nearly forty years ago now, Candoni was one of the remotest towns in Negros. It was a grueling two-hour journey into the mountains from Kabankalan. You had a choice: to go via Salong and Tapi or via Dancalan and Tabo. Either way it was a long journey and a hard road which reminded one in parts of pictures of the surface of the moon. The young priests have it a lot easier nowadays. I recall going there by bus and frequently deciding to travel on the roof, seated on sacks of rice or fertilizer rather than the cramped quarters inside. The only problem was that when we passed under trees we sometimes had to lie out flat lest we be swept off the roof by a low lying branch. As we approached a townlet we had to climb in through the windows while the bus was still moving because it was illegal to be traveling on the roof. My short stay in Candoni was caused by the fact that Fr. Eugene McGeough, the parish priest, was away on holidays in Ireland and I was to take his place.

I remember making a journey by horse (I, an untrained townie) to the place called Sawmill somewhere in the mountains. I had some trouble in getting that horse to cross the river. I was bringing the last sacrament to a woman who was dying. I recall her happiness that I had made the journey and my own peace of mind that I had been able to help her if even a little on her journey. But sadly, the trees are all gone now and indeed much of the soil too and many of the inhabitants had to go off to Palawan.

But I am wandering. Because what I really want to talk about is the then parish priest of Candoni, Eugene McGeough, and I am finding it difficult because he was so extraordinary and so different that I don’t know where to begin. Once Bishop Fortich after visiting the parish said that Gene was the most loved priest who ever lived in that difficult parish. I can vouch for this, but the question is why? He was not an organizer, a church builder, an initiator… though he did all these. What was he? He was a dear, dear friend to anyone who was willing to accept his friendship. He would spend hours talking to old lolas and lolos and he would regard them as his lola or lolo. The convento was packed with all sorts of people and if there were not enough blankets at night he would take down the curtains which his sister Mary, visiting from Ireland, had put up and use them as blankets for the people. He was a man with a tender heart and that was a difficult thing to be during the atrocities of the Marcos years. And I hope I hurt no one’s feelings when I say that a great number of people in the lowlands just did not believe us when we told them what was going on.

I think Gene was one of the first priests after Vatican II to gather a core group around him and listen to them and let them make the decisions for the parish. In this way, indirectly he was an initiator of many things. Power is a great temptation for any priest especially for a priest in a remote rural parish. Eugene never fell for that temptation. He listened carefully to everyone and usually let the group make the decision, treating everyone as equal and with a special ear for the poor…though he himself came from a privileged background.

On one occasion during the Marcos years, two Criminal Investigation Service (CIS) agents called to the convento. Presumably they had heard from local officials of Fr. Eugene’s complaints about how the army were behaving. “Have you any complaints, Father? Why don’t you just report them to us rather than to the public?” Eugene proceeded to tell them many stories, including one about how his sacristan’s mother had been raped and murdered by a group of cowboys, employees of a wealthy man in the lowlands. He couldn’t control his tears, which sort of threw the CIS agents who didn’t really take all of this too seriously. They were more interested in public relations than in helping, as was evidenced by the fact that they took down the details ‘on the back of an envelope’.

Fr. Eugene died on Saturday, 3rd of November last year, after a long battle with cancer. For the last few years he had been serving in the parish of Iona Road, Dublin. Just like Candoni the people fell in love with him, though he never promoted himself in anyway. Once again it was his ability to be present to people, to listen to them and to take care of them. The church was packed and after the Mass we spotted what for Ireland was an unusual sight…the altar girls huddled in the sacristy all in floods of tears trying to console each other.

The next day we had our own Mass for him in St. Columban’s Missionary College with Fr. Mark Kavanagh giving the sermon. Mark was parish priest of Kabankalan for many years and his sermon was really beautiful. I was so happy to be asked to say the Mass for my old and dear friend.

Fr. Eugene was buried here in St. Columban’s Missionary College in our special graveyard with missionaries from all over the world. His grave is beside of Fr. Eamonn Gill and Fr. Brendan O’Connell, both of whom worked with him in the mountains of Negros. If the young priests of Negros have the same heart for the poor as these three men then the future of the Church will be one of grace and peace.

Only the people of Candoni could tell you the real story of Eugene and I hope someday they will find a way to do it. I am not surprised that the present mayor and some of the councilors and government officials are his potégés and I would imagine some of his spirit has rubbed off on them. I do hope they put up some memorial to one of the most loved priest their town has ever had and I am sure that tears were shed in Candoni when they heard the news.

The Prostitutes Will Go Into Heaven Before Us

Sr Angela Battung RGS

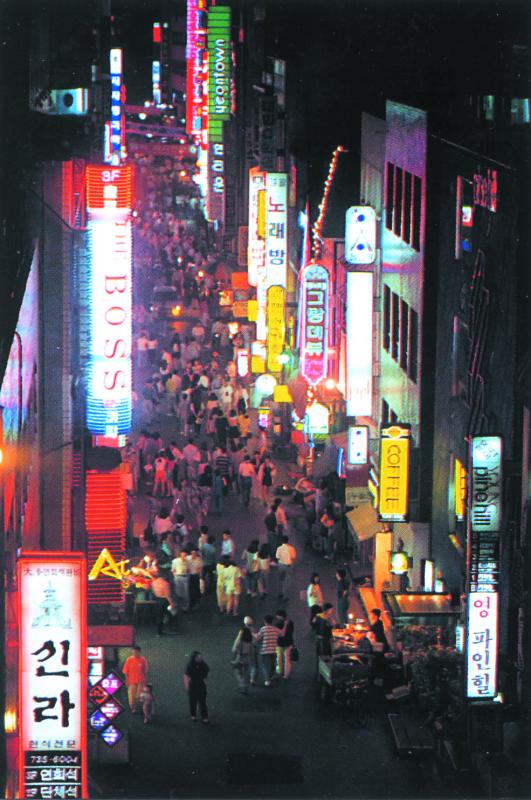

Sr Angela Battung, RGS has been a missionary most of her life. Now in Canada with older people, she looks back on her difficult years in Korea and the frustrating ministries she was involved in. Strangely enough it was at work with the prostitutes that grace almost became tangible and it was this work which she remembers with joy.

Sr Angela Battung, RGS has been a missionary most of her life. Now in Canada with older people, she looks back on her difficult years in Korea and the frustrating ministries she was involved in. Strangely enough it was at work with the prostitutes that grace almost became tangible and it was this work which she remembers with joy.

One of my first ministries in Korea was probably the most frustrating in my life. It was at a large American Base. I worked at the Chaplain’s office as a marriage counselor to American airmen marrying Korean women. Actually my work was to prepare the couples for the Sacrament of Matrimony. The women mostly were bar girls or prostitutes who wanted to go to the land of “unimagined wealth and luxury” or they just wanted free access to PX (imported) goods. The men were no better. Mostly they were those who never went to Mass or Services and cursed freely, hanging out at the Air Base Main Gate or the periphery. Some wanted to marry anyone they could use for black market. “We need an Asian, preferably Korean for the family whore house. Korean women are exotic spice for the flesh trade,” they would say. They had a variety of reasons for marrying. Some disgusting, others unbelievable, most were ‘business deals’. They were going to use each other. They both knew it, but who cared anyway? As long as they made money out of the union!

Bogus marriage

I told the chaplain, a tall, kind Catholic priest, it would be a mockery of the Sacrament of Matrimony to marry people who didn’t even believe it. I recommended a sort of marriage preparation course or orientation to the American lifestyle for the Korean women and understanding Korean women for the American men. They could get married elsewhere but not in our church. The priest chaplain and I came to an agreement.

American wannabes

The women, who did not speak English and could barely read and write, came with glossy and expensive American women’s magazines. They showed me pictures of big, beautiful Hollywoodmansions, expensive furniture, clothing, jewelry. They asked me to help them order the goods. I explained that it was not part of my job. I tried to tell them about the dangers of materialism. I also told them the truth – most of the young, almost teenaged GIs were not rich but just ordinary Americans. They would not believe me. I was “a nun and out-of-this-world!”

Consolation in the base

The bright and meaningful moments for me were the daily Masses at the tiny air base chapel or in our school, the communication with the staff at the Chaplain’s office. We were Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, black and white, male and female, priests, nuns, lay persons, military. We accepted and helped each other, trying our best to be Christians in a military base, always on the alert in case war broke out.

Concern for young women

The Good Shepherd Sisters to which I belong have always focused on abandoned women, single mothers and young women in trouble. Korea is no exception and my congregation asked me to change gear and work more closely with this group; similar but quite different from my work at the base. The women I was going to minister to were live-in partners of the GIs and had children calledhyon-no-rah or mixed blood. These children were not accepted; in fact they are rejected by a society that is dominantly Buddhist and a nation that prided itself in its purity and dislike for foreigners. One of our American sisters helped the children get adopted or sponsored by good and caring American families. I took care of the mothers who naturally wanted a secure future for their children but who grieved over having to give them up.

Korean home

We gathered in a tiny room, rented by one of the mothers. It was her home – receiving room, bedroom, dining room, recreation room, guestroom, all-purpose room. A coal briquette burning under the floor called ondol kept the room and the people in it warm, too warm sometimes, during winter. Since I was guest of honor, I was asked to sit right on top of the spot where the coal was burning. Occasionally one of the mothers would rub my hands and feet to keep my blood circulating. I wasn’t used to sitting cross-legged on the floor for a long time.

Eager searchers of God

In a corner of the room, there was a small wooden crucifix, strands of plastic flowers around its neck. A picture of the Blessed Virgin Mary was pasted on the wall. These were gifts from a missionary. Their love and reverence for Jesus and his mother were very touching. They wanted me to tell them about the Good News and tell stories of the miracles of healing and Jesus forgiving sinners. The Holy Spirit was pouring graces upon them and they were open and receptive.