Misyon Online - March-April 2014

Shahbaz Bhatti شہبازبھٹی

(9 September 1968 – 2 March 2011)

‘I want to live for Christ and it is for Him that I want to die.’

The Church in the Philippines is engaged in a nine-year preparation for the celebration in 2021 of the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Christianity in the Philippines in 1521. The first year of that preparation was the Year of Faith, 2013, observed throughout the world at the initiative of Pope Benedict XVI. The bishops of the Philippines have declared 2014, the second year of preparation for the celebration in 2021, as the Year of the Laity in the country.

Pope Francis in his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, The Joy of the Gospel (EG), calls each one of us to share that joy with others.

|

|

Back from Fiji, Part IIThe first part of this interview by Anne B. Gubuan, assistant editor, of Kurt Zion Pala appeared in the September-October issue of Misyon. Kurt is a Columban seminarian from Iligan City who last year completed his two-year First Mission Assignment in Fiji. He resumed his studies in theology last June. From what you’re saying, Fiji seems peaceful, with ‘unity in diversity’ and no conflict.

On the surface it’s peaceful. But you can feel the tension between the two cultures. You hear people’s biases, for example, ethnic Fijians saying that Indo-Fijians are ‘too frugal’. It’s like what I have experienced in Mindanao, between Christians and Muslims. But in Mindanao, everything is expressed, people fight. In Fiji, it’s a bit more repressed as people won’t discuss the situation among themselves.

|

|

|

In Prison in PeruBy Fr Noel Kerins Columban Fr Noel Kerins was ordained in Ireland in December 1965 and has spent most of his priestly life in Peru.

It was a hot and humid day. The jail is isolated and surrounded by sand. The prisoner's name was Peter; he was 22-years-old. I asked him his name, but he looked at the ground. His face was sad. He had just been baptized; his mother and sister had arrived for the ceremony. I had embarrassed him by asking for his father's name. In Peru, I would be called Noel Kerins Fitzgerald: both my father's and my mother's surnames are included. When Peter responded ‘My father never recognized me’ he suffered a double loss of face. He had only one surname, and now he had lost his honor, admitting that he was illegitimate, and that in front of a foreign priest.

|

|

|

Mission LimasawaBy Fr Hector Suano It was about ten in the morning and the sky was gray when I descended from the road to the shore. The sight and sound of big waves lashing the shore opened before me and the strong cold wind blowing against me made me adjust my feet for greater balance and stability. Beyond the waves not far away in the distance, I saw my destination island, emerald in color against the washed-out horizon. Knowing that boats would not travel in this stormy weather, I gave up my plan to visit it that day; crossing the sea was simply ‘Mission Impossible’.

The day before, I had gone to see Bishop Precioso D. Cantillas SDB of Maasin. I told him that I was interested in visiting a mission area of his diocese. He suggested Limasawa Island. You would never think that after almost 500 years of Christianity in the Philippines, Limasawa Island, where the first Mass was celebrated, would still be a mission area. But, for whatever reasons, this historic island remains very much a mission destination today.

|

|

Rattno's StoryFr McCulloch, an Australian, worked in Mindanao from 1971 till 1978 when he was assigned to Pakistan, a new mission for the Columbans. He spent 34 years in Pakistan and in 2012 was given that country’s highest civilian award for foreign nationals. He is now in Rome as the Procurator General of the Columbans.

Unlike three other children in his family, 12-year-old Rattno was lucky to survive in November 2012 when the shack their family called home burnt down. Rattno is a Hindu boy of the Parkari Koli tribal people in south-east Pakistan who are desperately poor, enslaved to feudal Muslim landlords, dispossessed, and who lost everything they had during the floods of 2010 and 2011. Rattno's parents moved to Jhirruk, 40km south of Hyderabad, when they heard that St Elizabeth Hospital was building houses to re-house flood affected people. Although the hospital had constructed 820 houses in other places, only 30 could be built in Jhirruk until more funds became available.

|

|

|

Tears and Light in JuarezBy Fr Kevin Mullins

Some time ago drug-cartel soldiers visited a house near our parish church. The man of the house was a small-time drug-seller and user. Reportedly he had not paid up on time. The cartel soldiers forced him and his three-year-old daughter to watch as they slit his wife’s throat. Then the child watched as they shot half her father’s face away and left him for dead. The little girl lay for nine hours on the legs of her dead parents and then, in the morning, went outside to let neighbors know that something was wrong. The violence of the drug cartels in our city is endemic but, for the cartels, it is a means to an end. They prefer their business to be free of violence and so use bribes to encourage collaboration from politicians, police chiefs, state governors, mayors, etc. These are often offered a choice: plata (money) or plomo (lead ie, a bullet).

|

|

|

Pulong ng Editor

Shahbaz Bhatti شہبازبھٹی

(9 September 1968 – 2 March 2011)

‘I want to live for Christ and it is for Him that I want to die.’

The Church in the Philippines is engaged in a nine-year preparation for the celebration in 2021 of the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Christianity in the Philippines in 1521. The first year of that preparation was the Year of Faith, 2013, observed throughout the world at the initiative of Pope Benedict XVI. The bishops of the Philippines have declared 2014, the second year of preparation for the celebration in 2021, as the Year of the Laity in the country.

Pope Francis in his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, The Joy of the Gospel (EG), calls each one of us to share that joy with others.

In EG 102 Pope Francis writes:‘Even if many are now involved in the lay ministries, this involvement is not reflected in a greater penetration of Christian values in the social, political and economic sectors. It often remains tied to tasks within the Church, without a real commitment to applying the Gospel to the transformation of society.’

A Catholic who embodied the commitment the Pope has in mind was a politician in Pakistan, where Columbans have been working since 1979, ShahbazBhatti, assassinated on 2 March 2011 in Islamabad, shortly after he had left his mother’s home.

The Spiritual Testament of Shahbaz Bhatti

A month after his death La Civiltà Cattolica, a Jesuit magazine in Rome the contents of which are inspected and authorized by the Vatican Secretariat of State, published the Spiritual Testament of Shahbaz Bhatti. Sandro Magister, one of the best known commentators on Vatican affairs, republished it on his blog. Here is the English translation as found there.

'My name is ShahbazBhatti. I was born into a Catholic family. My father, a retired teacher, and my mother, a housewife, raised me according to Christian values and the teachings of the Bible, which influenced my childhood. Since I was a child, I was accustomed to going to church and finding profound inspiration in the teachings, the sacrifice, and the crucifixion of Jesus. It was his love that led me to offer my service to the Church.

'The frightening conditions into which the Christians of Pakistan had fallen disturbed me. I remember one Good Friday when I was just thirteen years old: I heard a homily on the sacrifice of Jesus for our redemption and for the salvation of the world. And I thought of responding to his love by giving love to my brothers and sisters, placing myself at the service of Christians, especially of the poor, the needy, and the persecuted who live in this Islamic country.

'I have been asked to put an end to my battle, but I have always refused, even at the risk of my own life. My response has always been the same. I do not want popularity, I do not want positions of power. I only want a place at the feet of Jesus. I want my life, my character, my actions to speak of me and say that I am following Jesus Christ.

'This desire is so strong in me that I consider myself privileged whenever - in my combative effort to help the needy, the poor, the persecuted Christians of Pakistan - Jesus should wish to accept the sacrifice of my life. I want to live for Christ and it is for Him that I want to die. I do not feel any fear in this country. Many times the extremists have wanted to kill me, imprison me; they have threatened me, persecuted me, and terrorized my family.

'I say that, as long as I am alive, until the last breath, I will continue to serve Jesus and this poor, suffering humanity, the Christians, the needy, the poor. I believe that the Christians of the world who have reached out to the Muslims hit by the tragedy of the earthquake of 2005 have built bridges of solidarity, of love, of comprehension, and of tolerance between the two religions. If these efforts continue, I am convinced that we will succeed in winning the hearts and minds of the extremists. This will produce a change for the better: the people will not hate, will not kill in the name of religion, but will love each other, will bring harmony, will cultivate peace and comprehension in this region.

'I believe that the needy, the poor, the orphans, whatever their religion, must be considered above all as human beings. I think that these persons are part of my body in Christ, that they are the persecuted and needy part of the body of Christ. If we bring this mission to its conclusion, then we will have won a place at the feet of Jesus, and I will be able to look at him without feeling shame.'

Ooberfuse is a London-based band whose lead singer, Cherrie Anderson, is the daughter of a Filipina immigrant to Britain. The members of the band use music to share the Gospel and wrote His Blood Cries Out for the first anniversary of the death of ShahbazBhatti. They incorporated in the video part of a TV interview with the Pakistani politician about a month before he died. Here is the final part of that interview with a transcript below the video.

>

‘Minister Bhatti, you forgot one question in the interview. Your life is threatened by whom and what sort of threats are you receiving?’

‘The forces of violence, militant banned organizations, the Taliban, and Al Qaeda, they want to impose their radical philosophy on Pakistan. And whoever stands against their radical philosophy that threatens them, when I’m leading this campaign against the Sharia Law, for the abolition of the Blasphemy Law, and speaking for the oppressed and marginalized, persecuted Christian and other minorities, these Taliban threaten me.

‘But I want to share that I believe in Jesus Christ who has given his own life for us. I know what is the meaning of the Cross and I’m following of the Cross and I am ready to die for a cause. I’m living for my community and suffering people and I will die to defend their rights. So these threats and these warnings cannot change my opinion and principles. I will prefer to die for my principle and for the justice of my community rather than to compromise on these threats.’

+++

‘I want to live for Christ and it is for Him that I want to die.’

No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends (John 15:13, NRSVCE).

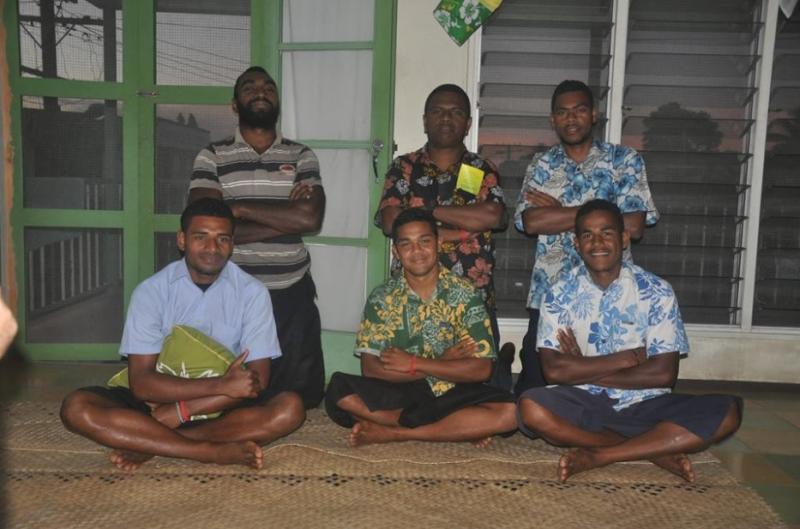

Back from Fiji, Part II

The first part of this interview by Anne B. Gubuan, assistant editor, of Kurt Zion Pala appeared in the September-October issue of Misyon. Kurt is a Columban seminarian from Iligan City who last year completed his two-year First Mission Assignment in Fiji. He resumed his studies in theology last June.

From what you’re saying, Fiji seems peaceful, with ‘unity in diversity’ and no conflict.

On the surface it’s peaceful. But you can feel the tension between the two cultures. You hear people’s biases, for example, ethnic Fijians saying that Indo-Fijians are ‘too frugal’. It’s like what I have experienced in Mindanao, between Christians and Muslims. But in Mindanao, everything is expressed, people fight. In Fiji, it’s a bit more repressed as people won’t discuss the situation among themselves.

So it’s a latent conflict?

Yes, and it bothers me. Sometimes if I behaved like an ethnic Fijian my Indo-Fijian friends would say, ‘You’re not Fijian, you’re Indian’. It was similar when I was with the ethnic Fijian community. So I had to balance everything and try not to take sides.

When with a community I tried too not to stay with one family only because others might get jealous. I tried to visit each house and would lose count of the cups of tea I had in one day. Even if I’d already eaten in one house I’d had to eat again in the next, not because I. don’t know how to say ‘No’ but out of respect. It’s part of the hospitality of the people that they give their visitor their best.

Here in the Philippines you can experience that also especially in rural areas.

Yes it’s like that here. Even if it’s the first time they’ve met you, people in Fiji feel that you’re already close. In their language there’s a specific way to address each other. In order for people to feel comfortable with me I learned and studied that dynamic. I called my foster-father, ‘Nana’ and my foster-mother, ‘Nani’. There are also specific ways to address specific terms of address for the siblings and relatives of one’s Nana and Nani. I familiarized myself with these terms and when I used them my friends accepted me in their homes without any fuss.

How about vocations to the priesthood there? Is there a chance of more?

So far, I think, only five Fijians have become Columban priests. Indo-Fijian men are expected to marry and arranged marriages are part of their culture. So a man doesn’t have much choice even if he desires to become a priest.

In my foster-family I had a brother, the only boy, and many encouraged him to become a priest. But he would always hold back. When I would ask Nani ‘What about Laurence, if he wants to become a priest?’ I could feel her hesitation and she’d just say, It’s alright, you’re there anyway’.

In the ethnic Fijian community a priest has many privileges. They hold the priest in such high esteem that they insist on serving them. This affects missionary vocations because some Fijians who want to be priests want to stay in Fiji.

When I was there I would spent time with the youth and try to get across the idea that it’s wonderful to be a missionary. Sometimes Fr Frank Hoare would let me conduct a search-in.I would tell participants that the priesthood is not just in Fiji. You could be sent to the Philippines or some other countries.

What the Columbans are doing is simple. They go to their respective mission places, get immersed in the people and live their faith. You don’t have to ‘do’ or talk so much. People just see how you live.

That’s exactly why I was chided by my supervisor. I got so familiar with what I was doing that I tried ‘expanding’ my ministry with the youth. The Columbans wanted me to focus on ministry to the Indo-Fijians. But I could see a great need to work with the youth. I was a bit disheartened to see them ready, willing and available but with no priest to work with them. So I tried spending time with them.

That’s when I got a good chiding from my director. Up to my last day in Fiji he kept hammering away about the choices I made.. But I think he eventually appreciated that there was a part of me that wasn’t really rebellious but just wanted to make some decisions on my own. In the end he gave up and told me, ‘You are trying not to prove yourself, but just trying to make decisions for yourself’.

Was that a good or a bad thing?

I took it as a good thing that he saw it that way because I felt I had grown from that process. I knew that I should be conscious of the word ‘obedience’ in the path I had chosen. But it shouldn’t be a blind obedience. I saw a need, and responded to that. I also checked myself: ‘Is this MY personal need?’ What’s beautiful about First Mission Experience (FMA) is that you’re given freedom at a certain point but also guidance. That’s why I am very grateful to Father Frank. By the time my FMA ended it became clear to me what I really wanted.

One of my classmates said to me one time, ‘Home is where your heart is’. That’s when I realized that I was already at home in Fiji. So it was difficult when it was time for me to leave because it wasn’t ‘going home’ for me but rather like ‘leaving home’.

Fr Niall O’Brien said something like that too about leaving Ireland and coming back to the Philippines: ‘The feeling is ambivalent. I am leaving home, and I am coming home.’ That is such a beautifully poignant kind of experience and you are so privileged.

When you board the plane, you shouldn’t look back. I tried looking back and was sure I wouldn’t able to go at all, that I might run back. So I went straight to the plane without looking back. It was so painful. I could still see the looks on the faces of my Indo-Fijian family, especially Nana, whom I considered a real father. Days prior to my leaving, he wouldn’t talk to me, wouldn’t even look at me. But on my last day he suddenly gave me a hug and cried on my shoulder. I can never get over that moment when I knew I just had to go, no matter how much I had grown to love these people as my own family. What made it even more painful was that I know how hard it was for them too.

I was already spreading my roots in Fiji and felt like a tree being uprooted. I comfortable going around the town, I knew everyone already and everyone knew me. I was already living a normal life there. In the beginning I had felt a total stranger, with people looking at me from head to foot. I was a foreigner to them. After two years there I was ‘an ordinary citizen’ there, like the people who lived there.

I started to question if I was losing my effectiveness as a missionary. They were so at home with me already that they wouldn’t take me seriously anymore. I had so become one of them already that it seemed that we had the same color and language. Before, I would stay five minutes outside a store rehearsing my lines. But now I surprised myself with how spontaneous I had become in conversation, with the way I was dealing with the people. I consider this a little ‘miracle’. No matter how old you are you can still learn a new language as long as you’re open to challenges and possibilities. I consider all these things a very big adventure.

Pope Francis in his first homily as pope said, ‘My wish is that all of us . . . will have the courage . . . to walk in the presence of the Lord, with the Lord’s Cross’. Was there a point in your vocation journey when somehow you got afraid of the Cross? How did you get over it?

Yes there was, when my father died in an accident at work. I was already in the seminary. My initial reaction was, ‘Why did this happen to me? Every day I prayed for him to be safe always’. So there were so many ‘whys’ for me that time. ‘Why did this happen to my father? What did I do to deserve this?’ We were only starting to know each other. The irony was we’d waited till I was an adult and my father was getting old for us to get to know each other. We didn’t have the chance to do that when I was little.

When I entered the seminary I realized the importance of building relationships with my family, especially with my father. So I struggled a lot when he died. Even if you have given your whole self to God, there is still something that he will take from you, something that was hard for me to understand. But it was through this that I started to understand the mystery of the Cross and that’s when I became closer to God. God will never give you the Cross without the grace to carry it. We missionaries live by that reality.

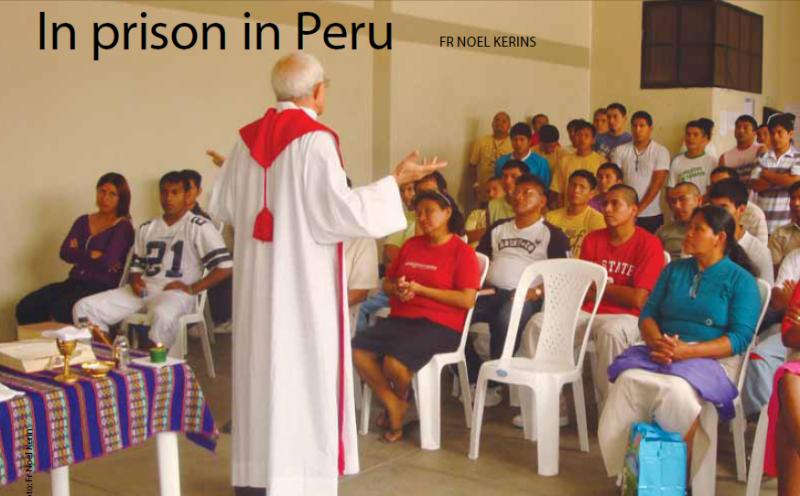

In Prison in Peru

by Fr Noel Kerins

Columban Fr Noel Kerins was ordained in Ireland in December 1965 and has spent most of his priestly life in Peru.

Columban Fr Noel Kerins and his prison team at a Mass for prisoners.

It was a hot and humid day. The jail is isolated and surrounded by sand. The prisoner's name was Peter; he was 22-years-old. I asked him his name, but he looked at the ground. His face was sad. He had just been baptized; his mother and sister had arrived for the ceremony. I had embarrassed him by asking for his father's name.

In Peru, I would be called Noel Kerins Fitzgerald: both my father's and my mother's surnames are included. When Peter responded ‘My father never recognized me’ he suffered a double loss of face. He had only one surname, and now he had lost his honor, admitting that he was illegitimate, and that in front of a foreign priest.

Perhaps to some this episode might appear trivial. Eight years as a prison chaplain in Lima has taught me otherwise. The vast majority of those in that prison - in all 3,600 - are victims before they victimize others.

In Peter's case, his single mother was the bread-earner of his home. She worked a 12-hour day for the equivalent of US$10 dollars a day. His sisters, one five years older than he, the other three, looked after and nourished him from the outset.

Need I say more? Attempt to walk in those shoes for 22 years: I honestly believe I would have fared much worse than Peter. There are 57,529 prisoners in Peru's 66 jails. Two-thirds of them have not received a sentence.

On being accused they are jailed ‘as a precautionary measure’. In practice this means that a prisoner can be four, five or six years in jail, while being innocent. One of the tasks that we do is to try and locate a piece of paper (called ‘expediente’) so that legal proceedings may begin. This is a tedious and painstaking task that requires time, dedication and endless patience.

On being accused they are jailed ‘as a precautionary measure’. In practice this means that a prisoner can be four, five or six years in jail, while being innocent. One of the tasks that we do is to try and locate a piece of paper (called ‘expediente’) so that legal proceedings may begin. This is a tedious and painstaking task that requires time, dedication and endless patience.

If the prisoner is not from Lima it also requires travel. Even having found it, legal proceedings are painfully slow. At each step payment is required. The partner is generally poor and trying to look after two or three children.

Over half the total prison population is imprisoned in Lima and overcrowding is the norm. The population capacity of Peru’s jails is 28,689: the total prison population is twice that figure. Corruption is endemic in the system. From the smallest detail, eg, where a bed is placed, to the severity and extent of the sentence, everything is influenced by who I know and how much I am prepared to pay. One prisoner put it very succinctly to me one day as we spoke, ‘With $10,000 I could be out of here within two weeks’.

A prison ombudsman (‘fiscal’) certified after due process that the food served in the jail we visit is not fit for human consumption. To move on that fact - verified by the competent authority - would require, perhaps, three years. It would certainly require more political will than exists at present.

In fact family members nourish the prisoners. Hundreds of kilos of food are brought to the prison on each visiting day. In the two jails that we visit there are 3,600 prisoners, 500 or them women.

In fact family members nourish the prisoners. Hundreds of kilos of food are brought to the prison on each visiting day. In the two jails that we visit there are 3,600 prisoners, 500 or them women.

In both jails there is, technically, a small office for health care. It exists but, in practice, it is purely nominal. By way of illustration, I had two operations for a particular health problem during the last four years.

I received the best of care. With all that I was still recuperating with medication for the best part of six weeks. In the prison I came across one prisoner who suffers from the same condition. He receives not as much as an aspirin!

The paper work (‘tramites’) to actually get the medical team to the jail would take at least a year and a day. The same goes for tuberculosis, AIDS, or any other condition. So, the picture is indeed bleak.

What then can we do? Well we are a group of 33 members who pledge to visit the jail, in pairs, on one morning or afternoon each week. We offer a human face within an inhuman system. We chat about normal life happenings, a birthday, a visit from a friend, a death in the family.

We share a reflection on the words and the actions of Jesus for those who wish it. We assist the poorest prisoners to locate the above-mentioned expediente, so important since two-thirds are jailed without a sentence.

We celebrate the Eucharist on important occasions, Holy Week, Christmas, on significant feasts, or on the death of a relative. We facilitate education programs, recognized by the Government, so that some may be motivated to continue their basic primary and secondary education. With the help of a professional medical team, we do a screening for tuberculosis and AIDS once every year.

In the Gospels, we don't read that Jesus visited a jail in his homeland, but he did remind us that one of the tests we will face before the final curtain falls will be, ‘I was sick and imprisoned and did you visit me?’

Mission Limasawa

By Fr Hector Suano

It was about ten in the morning and the sky was gray when I descended from the road to the shore. The sight and sound of big waves lashing the shore opened before me and the strong cold wind blowing against me made me adjust my feet for greater balance and stability. Beyond the waves not far away in the distance, I saw my destination island, emerald in color against the washed-out horizon. Knowing that boats would not travel in this stormy weather, I gave up my plan to visit it that day; crossing the sea was simply ‘Mission Impossible’.

The day before, I had gone to see Bishop Precioso D. Cantillas SDB of Maasin. I told him that I was interested in visiting a mission area of his diocese. He suggested Limasawa Island.

You would never think that after almost 500 years of Christianity in the Philippines, Limasawa Island, where the first Mass was celebrated, would still be a mission area. But, for whatever reasons, this historic island remains very much a mission destination today.

Limasawa is off the southern tip of Leyte and is seven square kilometers in area with a population of fewer than 6,000. It is a sixth class town divided into six barangays. Fishing and arming are the main sources of livelihood, dried squid and fresh bananas being the island’s most popular products.

Due to its isolation, the people of Limasawa enjoy few comforts in life. But its resources, which they acknowledge as God's blessings, keep them going.

Failing to cross the sea, I phoned Fr Christopher B. Esquibel, the parish priest of Holy Cross and the First Mass Parish, which includes the whole island, to learn more about life there and why it is considered a mission area. He said that the people on the island have and treasure their faith in God but that they have an issue on which faith group to affiliate to.

Currently, there are 14 faith groups on the island. About half of the population is Catholic while the rest belong to smaller faith groups.

Father Cris found that the faith of the Catholics needs to grow and make deeper roots. He calls for a ‘Duc In Altum’ – ‘Launch out into the deep’ approach to the faith.

The story of the Limasawans is our story too. Like them, we constantly struggle to witness to our faith in the situations in which we find ourselves. And Father Cris needs assistance in his campaign to encourage the deepening of faith in his people. If you have the time, talent, and treasure to help Father Cris you are most welcome to do so.

Some of our islands need missionaries from other islands in order to develop and grow in our Catholic Christian faith and to be closer to becoming ‘bright spots of heaven’ on earth.

The dark and low clouds burst and the heavy rain fell down like stage curtains slowly covering the island from my view when I left the shore. As I hop on the vehicle to be on the road again to visit other mission areas, I prayed that God may send missionaries to Limasawa Island.

***

Rattno's Story

Fr McCulloch, an Australian, worked in Mindanao from 1971 till 1978 when he was assigned to Pakistan, a new mission for the Columbans. He spent 34 years in Pakistan and in 2012 was given that country’s highest civilian award for foreign nationals. He is now in Rome as the Procurator General of the Columbans.

Unlike three other children in his family, 12-year-old Rattno was lucky to survive in November 2012 when the shack their family called home burnt down. Rattno is a Hindu boy of the Parkari Koli tribal people in south-east Pakistan who are desperately poor, enslaved to feudal Muslim landlords, dispossessed, and who lost everything they had during the floods of 2010 and 2011.

Fr Robert McCulloch and hospital administrator James Francis talk about the involvement of the Missionary Society of St Columban in St Elizabeth Hospital.

Rattno's parents moved to Jhirruk, 40km south of Hyderabad, when they heard that St Elizabeth Hospital was building houses to re-house flood affected people. Although the hospital had constructed 820 houses in other places, only 30 could be built in Jhirruk until more funds became available.

The hope of Shivji and Shonti, Rattno's parents, turned to disaster when their children were lighting a kerosene pressure lamp which exploded. Saiba, Lakhnu and Shonti, aged from 7 to 15, died in the fire. Rattno survived.

St Elizabeth Hospital arranged for Rattno's extensive skin grafts and medical care. He has recovered well from the skin grafting procedures. St Elizabeth wants to continue his good medical care, to ensure infection control and to provide the food and comfort which he would not get in the desert settlement of Jhirruk. His parents take turns in remaining at the hospital with him.

Happiness and hope have come back to Rattno. I often say to myself: ‘If only we had the money then to build all the houses in Jhirruk so that Rattno and his family would have a permanent home!’

The skin grafting on Rattno's legs, face and left hand is a success. He had the first orthopedic surgery on his left leg on 17 January this year. This was successful. At the time of writing he was due to have two more surgical procedures in February. The cost of his care will be close to Php400,000. He was able to begin his school education in May last year while still in hospital.

None of the other 540 adults, teenagers and children living in the permanent houses in Jhirruk or still waiting for their houses to be built has been to school.

We know that Rattno's story will have a happy ending as he recovers. We hope that it will see a new beginning through education for him and the children of his village.

This article appeared in the September 2013 issue of The Far East, the magazine of the Columbans in Australia and New Zealand.

Tears and Light in Juarez

By Fr Kevin Mullins

The author is a Columban from Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, who has worked in Chile and in Britain. For the past fifteen years he has been in Corpus Christi Parish, Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico, just across the border from El Paso, Texas, USA. The parish, along with a presence in El Paso, is part of the Columban Border Ministries of the Region of the United States.

The author is a Columban from Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, who has worked in Chile and in Britain. For the past fifteen years he has been in Corpus Christi Parish, Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico, just across the border from El Paso, Texas, USA. The parish, along with a presence in El Paso, is part of the Columban Border Ministries of the Region of the United States.

A news report on 7 News, Australia, 2012

Some time ago drug-cartel soldiers visited a house near our parish church. The man of the house was a small-time drug-seller and user. Reportedly he had not paid up on time. The cartel soldiers forced him and his three-year-old daughter to watch as they slit his wife’s throat. Then the child watched as they shot half her father’s face away and left him for dead. The little girl lay for nine hours on the legs of her dead parents and then, in the morning, went outside to let neighbors know that something was wrong.

The violence of the drug cartels in our city is endemic but, for the cartels, it is a means to an end. They prefer their business to be free of violence and so use bribes to encourage collaboration from politicians, police chiefs, state governors, mayors, etc. These are often offered a choice: plata (money) or plomo (lead ie, a bullet).

The primary focus of the cartels is transporting illegal drugs from Mexico to the USA. It affects us directly because the traffic comes through Ciudad Juárez, our city, on the way across the USA/Mexico border into El Paso. Government authorities at all levels, including the police and military, Non-Government Organizations and Catholic Church leaders have consistently shown by their actions that they do not believe that the cartel-based drug business can be brought under control or eliminated solely by repressive means. In the face of the demand for illicit drugs from within the USA and the huge profits to be made, no institution of the State, civil society or the Church has been able to come up with an effective proposal for moving against this lethal business.

Up until recently an average of 15 people were being killed each day in the Juárez area. The Sinaloa artel defeated the Juárez cartel and in so doing gained control of access to the USA through Juárez. These days the killing is down to an average of five people a day as control of the illicit drug business is exercised by the simple logic of reward (money) or punishment (execution). With the Sinaloa cartel firmly in control, business is booming. So, one might ask: How do we go about shaping our lives in this far from perfect society? Is it enough to simply avoid becoming directly involved in drug trafficking? Can we be authentic and yet refuse to tackle this pernicious evil in our midst?

The recent end of the inter-cartel conflict has allowed new signs of life to emerge in the city. The construction industry is quite active. People are going out more to restaurants, night-clubs, dance-halls and theaters. The atmosphere of constant fear is nowhere near as heavy as it used to be. The people of our parish, our diocese and our city look for ways of making sense of their lives despite the context of violence, greed, corruption and brutal injustice.

We are sadly aware that there is so much that we cannot change and yet we are determined to find a way to live authentically in the midst of terrible evil. We have a vibrant parish where we recently celebrated the First Communion of 150 children and the Confirmation of 120 youth. We sent our Confirmation group on an ‘Extreme sports’excursion to open them up to life and adventure outside the poverty of our parish on the fringe. We held a parish mission with faith renewal sessions for participants. Our parish community continues to grow in numbers and one important thing I have noted recently is the increasing mutual respect between youth and adults.

I see our parish and our diocese as beacons of hope for life. We realize of course that we will not ‘put things right’ but we are helping our parishioners grow in resilience, mutual respect and creativity. Our diocese constantly proclaims a message of dignity and hope. Recently the diocese convoked 11,000 youth to participate in a two-day Congress calling to conversion, and emphasizing the value of life. We do not take up the cudgels against all that the drug cartels stand for, but we do propose a different set of values; we offer an alternative way of living.

Catedral de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, Ciúdad Juarez

The more I see the parish community grow the more I sense that the Church’s liturgical cycle offers parishioners a stable framework for their lives. I don’t think we offer an escape from a pernicious social reality but rather a viable, alternative value system. We would be grateful for your prayers and for any material assistance you can offer to help us in our task.

Fr Kevin Mullins featured on PBS (Public Broadcasting Service) Television, USA, 26 March 2010

Radio interview with Fr Mullins

On 11 January 2013 Father Kevin was featured on National Public Radio in the USA. You may listen to the report here.

Editor’s note: The leader of the Sinaloa cartel mentioned in the article, Joaquín Guzmán Loera, known as ‘El Chapo’ or ‘Shorty’, was arrested on 22 February in Sinaloa in a joint operation by Mexican and US authorities. He was then taken to Mexico City. He was perhaps the most powerful drug lord in history.