Back from Fiji, Part II

The first part of this interview by Anne B. Gubuan, assistant editor, of Kurt Zion Pala appeared in the September-October issue of Misyon. Kurt is a Columban seminarian from Iligan City who last year completed his two-year First Mission Assignment in Fiji. He resumed his studies in theology last June.

From what you’re saying, Fiji seems peaceful, with ‘unity in diversity’ and no conflict.

On the surface it’s peaceful. But you can feel the tension between the two cultures. You hear people’s biases, for example, ethnic Fijians saying that Indo-Fijians are ‘too frugal’. It’s like what I have experienced in Mindanao, between Christians and Muslims. But in Mindanao, everything is expressed, people fight. In Fiji, it’s a bit more repressed as people won’t discuss the situation among themselves.

So it’s a latent conflict?

Yes, and it bothers me. Sometimes if I behaved like an ethnic Fijian my Indo-Fijian friends would say, ‘You’re not Fijian, you’re Indian’. It was similar when I was with the ethnic Fijian community. So I had to balance everything and try not to take sides.

When with a community I tried too not to stay with one family only because others might get jealous. I tried to visit each house and would lose count of the cups of tea I had in one day. Even if I’d already eaten in one house I’d had to eat again in the next, not because I. don’t know how to say ‘No’ but out of respect. It’s part of the hospitality of the people that they give their visitor their best.

Here in the Philippines you can experience that also especially in rural areas.

Yes it’s like that here. Even if it’s the first time they’ve met you, people in Fiji feel that you’re already close. In their language there’s a specific way to address each other. In order for people to feel comfortable with me I learned and studied that dynamic. I called my foster-father, ‘Nana’ and my foster-mother, ‘Nani’. There are also specific ways to address specific terms of address for the siblings and relatives of one’s Nana and Nani. I familiarized myself with these terms and when I used them my friends accepted me in their homes without any fuss.

How about vocations to the priesthood there? Is there a chance of more?

So far, I think, only five Fijians have become Columban priests. Indo-Fijian men are expected to marry and arranged marriages are part of their culture. So a man doesn’t have much choice even if he desires to become a priest.

In my foster-family I had a brother, the only boy, and many encouraged him to become a priest. But he would always hold back. When I would ask Nani ‘What about Laurence, if he wants to become a priest?’ I could feel her hesitation and she’d just say, It’s alright, you’re there anyway’.

In the ethnic Fijian community a priest has many privileges. They hold the priest in such high esteem that they insist on serving them. This affects missionary vocations because some Fijians who want to be priests want to stay in Fiji.

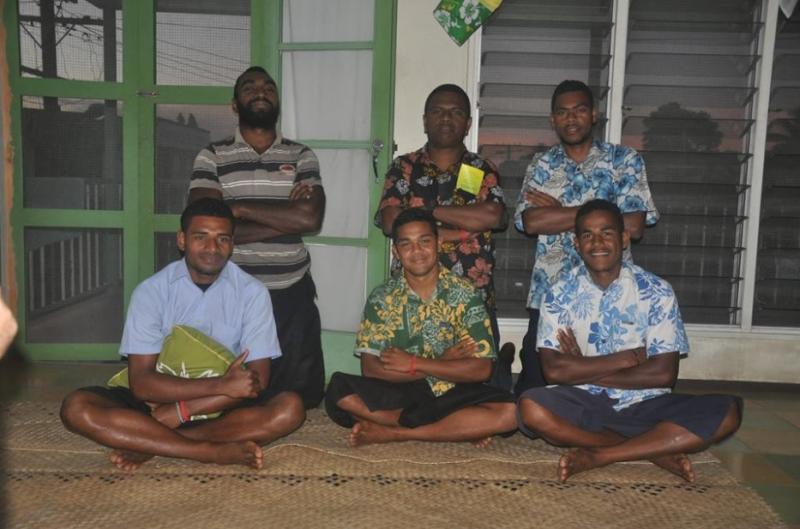

When I was there I would spent time with the youth and try to get across the idea that it’s wonderful to be a missionary. Sometimes Fr Frank Hoare would let me conduct a search-in.I would tell participants that the priesthood is not just in Fiji. You could be sent to the Philippines or some other countries.

What the Columbans are doing is simple. They go to their respective mission places, get immersed in the people and live their faith. You don’t have to ‘do’ or talk so much. People just see how you live.

That’s exactly why I was chided by my supervisor. I got so familiar with what I was doing that I tried ‘expanding’ my ministry with the youth. The Columbans wanted me to focus on ministry to the Indo-Fijians. But I could see a great need to work with the youth. I was a bit disheartened to see them ready, willing and available but with no priest to work with them. So I tried spending time with them.

That’s when I got a good chiding from my director. Up to my last day in Fiji he kept hammering away about the choices I made.. But I think he eventually appreciated that there was a part of me that wasn’t really rebellious but just wanted to make some decisions on my own. In the end he gave up and told me, ‘You are trying not to prove yourself, but just trying to make decisions for yourself’.

Was that a good or a bad thing?

I took it as a good thing that he saw it that way because I felt I had grown from that process. I knew that I should be conscious of the word ‘obedience’ in the path I had chosen. But it shouldn’t be a blind obedience. I saw a need, and responded to that. I also checked myself: ‘Is this MY personal need?’ What’s beautiful about First Mission Experience (FMA) is that you’re given freedom at a certain point but also guidance. That’s why I am very grateful to Father Frank. By the time my FMA ended it became clear to me what I really wanted.

One of my classmates said to me one time, ‘Home is where your heart is’. That’s when I realized that I was already at home in Fiji. So it was difficult when it was time for me to leave because it wasn’t ‘going home’ for me but rather like ‘leaving home’.

Fr Niall O’Brien said something like that too about leaving Ireland and coming back to the Philippines: ‘The feeling is ambivalent. I am leaving home, and I am coming home.’ That is such a beautifully poignant kind of experience and you are so privileged.

When you board the plane, you shouldn’t look back. I tried looking back and was sure I wouldn’t able to go at all, that I might run back. So I went straight to the plane without looking back. It was so painful. I could still see the looks on the faces of my Indo-Fijian family, especially Nana, whom I considered a real father. Days prior to my leaving, he wouldn’t talk to me, wouldn’t even look at me. But on my last day he suddenly gave me a hug and cried on my shoulder. I can never get over that moment when I knew I just had to go, no matter how much I had grown to love these people as my own family. What made it even more painful was that I know how hard it was for them too.

I was already spreading my roots in Fiji and felt like a tree being uprooted. I comfortable going around the town, I knew everyone already and everyone knew me. I was already living a normal life there. In the beginning I had felt a total stranger, with people looking at me from head to foot. I was a foreigner to them. After two years there I was ‘an ordinary citizen’ there, like the people who lived there.

I started to question if I was losing my effectiveness as a missionary. They were so at home with me already that they wouldn’t take me seriously anymore. I had so become one of them already that it seemed that we had the same color and language. Before, I would stay five minutes outside a store rehearsing my lines. But now I surprised myself with how spontaneous I had become in conversation, with the way I was dealing with the people. I consider this a little ‘miracle’. No matter how old you are you can still learn a new language as long as you’re open to challenges and possibilities. I consider all these things a very big adventure.

Pope Francis in his first homily as pope said, ‘My wish is that all of us . . . will have the courage . . . to walk in the presence of the Lord, with the Lord’s Cross’. Was there a point in your vocation journey when somehow you got afraid of the Cross? How did you get over it?

Yes there was, when my father died in an accident at work. I was already in the seminary. My initial reaction was, ‘Why did this happen to me? Every day I prayed for him to be safe always’. So there were so many ‘whys’ for me that time. ‘Why did this happen to my father? What did I do to deserve this?’ We were only starting to know each other. The irony was we’d waited till I was an adult and my father was getting old for us to get to know each other. We didn’t have the chance to do that when I was little.

When I entered the seminary I realized the importance of building relationships with my family, especially with my father. So I struggled a lot when he died. Even if you have given your whole self to God, there is still something that he will take from you, something that was hard for me to understand. But it was through this that I started to understand the mystery of the Cross and that’s when I became closer to God. God will never give you the Cross without the grace to carry it. We missionaries live by that reality.