Soul-Sisters – The Myanmar Connection

Two vibrant women, one aged 85 and the other 84 share stories of how the children ofMyanmar (Burma) bonded them. Burma was renamed ‘Myanmar’ in 1989.

A Buddhist temple in Yangon, Myanmar's capital city. Eighty-nine percent of people in Myanmar are Buddhist.

Daphne Tun Baw (85) tells her story.

I was born in Thaton, Mon Division, Burma in 1921, and my sister, Violet, less than two years later. My mother died when I was five and my father when I was nine. When he died, our grandparents and two aunties and an uncle from my mother’s side looked after us. We both started kindergarten when I was nine and my sister was seven. When I finished Grade Seven I was already 17. I trained as a teacher for one year and volunteered to teach children in a remote village for a year. I then transferred to the Paan (Baptist) mission school. I was 21 when the Japanese bombed Rangoon and World War II started for us.

All from the cities evacuated to the hills. We teachers continued to do mission work - Sunday School from nursery to the elders, choir and Bible recitation. Every month we went to different villages to have Christian Endeavor and Women’s Meetings. One headman led 15 villages, twelve Christian and three Buddhist. We had no money but didn’t feel hunger. The people gave us food because we taught their children.

When the war ended four years later, I returned to my birthplace and taught at the A.B.M. Karen High School from 1945-48. When Burma became independent from Britain in 1948 the Karen Revolution started, for recognition of the rights of the Karen Ethnic People. Most of the young Karenni men who had been in the Burmese Army, Navy and Air Force joined the revolution. There I met a young wireless operator. We promised to marry when the revolution was over.

I followed my auntie and set up a school in Kyun Wine Village. We had no salary but were happy to help our poor Karen people. They were Buddhists and animists. They didn’t know Jesus. They worshipped their ancestors, the god of trees, the god of forests, of mountains. From 1949 to 1953 I never saw my boyfriend. He was able to send a message to me by wireless only once each year on my birthday. In May 1954 Daniel came to my village with a pastor and a wedding ring. I was busy with teaching and didn’t want to marry, but my auntie agreed to his request because he was a decent man from a Christian family, and also faithful and honest to his promises. We married that month.

After a week he went to a village where his father had a farm and hired men to clear the land to build a house so I could teach there and he could farm. After just one hour of work he vomited blood. He had tuberculosis and needed hospital treatment. It was dangerous for him to go to Rangoonbecause he would be arrested there. He was cared for in the Moulmein Mission Hospital, but had to wait a month for a vacancy. I wanted to be with him but the Karen leaders didn’t want me to leave the school. After discussing it for two weeks, they finally agreed. ‘She worked for five years without salary. As a gift we should give her leave, whether she comes back or not.’ They arranged for two elephants, one for me and the other for the woman guide. My husband’s care cost 150 kyats per month for everything, including food and medicine. Each of his brothers and sisters gave 30 kyats per month. Since I had no salary, I wasn’t asked to contribute – but I wanted to work so I could help. Besides, I wasn’t used to not being busy.

I got a job as a clerk in the Customs Department in Rangoon – offering more than three times the ordinary salary. But my sister-in-law came from Syriam and asked me to teach in St. George Diocesan High School. Since I wanted to teach and was not interested in just earning money, I chose to teach there, and was able to help pay for my husband’s treatment. He was hospitalized for two years and came back to me in 1956. Our first son was born in 1957. Then from 1959 to 1962 he studied in theBible College and got a certificate. Our second son was born in 1960.

From 1963 to 1974 he was invited by Dr Gordon Seagrave, a medical doctor and surgeon from theUSA and a Baptist Missionary in Namkhan, Northern Shan State, to be pastor in the mission. While there, I taught in the high school, and my husband was ordained in 1973.

During those ten years he worked hard. His tuberculosis was cured, but he developed diabetes and high blood pressure. In April 1974 he went to Meiktila for a meeting of the Upper Burma Karen Association, and got very sick on the way back. He went to a monks’ hospital in Pyinmana where the nurses had been his church members, trained by Dr Seagrave. The nurses wanted to send a message to me, but he didn’t agree; it was a two day journey by train for me to come. He died the day I received the message. When I reached Pyinmana the supervisor opened the grave to show me his body. He seemed to be sleeping. He was 51 years old. The doctor apologized, but I told him, ‘It’s not your fault. It is God’s will.’

My two sons, then 14 and 17, went to Rangoon to study. The elder joined the revolutionary army after he graduated from Grade Ten. He was 19. My second son joined the revolutionary army in 1980 when he was 20, after he finished his studies.

I officially retired from teaching in 1983, but continued for three more years. My younger son came to ask me to teach in the Karen camp to help the children. ‘You helped the Burmese Government for 40 years. Now it’s time to help the Karens,’ he said. So in 1985 I took a plane to Tavoy, rode by car for a day, walked two more days across the mountains, then rode another whole day by boat to reach the Karen camp at Methame.

I started teaching in high school right away, but got sick with malaria the next month. The camp was in a mountain jungle. I worked with the ‘revolution children’ from 1985 to 1997. In 1997 the Burmese Army occupied the area and destroyed our camp and villages. We had to flee to the Thai border, to a village called Pu Mong.

A Thai military commander from the 9th Division came to the village with some soldiers informing us that all of us had to return. Our Karen elders and church leaders told him, ‘We can’t go back. The Burmese soldiers will kill us.’ The commander said, ‘They promised they won’t kill you.’ But our leaders said, ‘Don’t believe them. They say one thing, but act differently!’ The commander got angry and said there was no place for us to stay, unless we wanted to stay in the sea.

When I saw how angry he got, I felt I needed to speak. I looked at the commander and told him without an interpreter, in English: ‘Colonel, I am very happy to go back to my land, but I can’t go back now. It is war time and nobody can protect us. We never believe the Burmese. They say one thing, but they never do as they say. We fought the Burmese until now. Our forefathers had to fight all the time to defend our lives and basic rights. As we consider our future, we need to escape and stay in a neighboring country for a while. We considered staying in India, China, Indo-China and Laos but we can’t. Their religion and culture are very different. But Thailand is not very different. The religion may be different because Thais are Buddhist (the Karen are Christian), but the Thai people obey Buddha who taught them to be like Christ. Buddha taught them to obey the Lord, to love their neighbors, to help the poor, to help those who need your help, to feed those who are hungry – the same as Christ taught us. That’s why we have come here . . .’

He became quiet, then replied, ‘You can stay as long as you wish. You can stay until the war is ended.’

Then I added, ‘I want to open a school . . . it’s not fair to let the children be sad and unhappy.’

‘All right,’ he said. “You can open a school and teach what you think is good.’ So I went to a store and took the empty cardboard boxes to use as blackboards. I made stands with bamboo and used these as desks. I used plastic for roofing and as mats to sit on. Someone from the United Nations visited. A few days later, ten teachers from Bangkok came and interviewed me about the time I came fromBurma and chose to become a refugee so I could set up the school. They were amazed at what we were able to do with almost no materials.

After that we moved to Tham Hin Refugee Camp where the NGOs and COERR (Church Organizations for Emergency Relief for Refugees) provided what we needed for the school.

In February 2000 I got very sick and was brought to a Thai hospital for surgery. Because I was so weak, they had to give me intravenous fluids. My Thai doctor visited me every day after duty and would bring me milk and eggs from his home. A new doctor substituted for him on Sunday and asked me, ‘Pee Wee,’ (my nickname, because I am so small), are you a Christian? I saw copies of the Guide Post, Daily Bread and Home Chat by your bed.’ When I told him I was a Christian, he said that on Christmas Day the Pastor told him he could pray for anything he wished. So he and his companions prayed for me. I had successful surgery.

While there, the patients learned I could speak English, but not Thai. They sent their children to me, and I would teach them for ten or fifteen minutes at a time. I became friends with the doctors, the nurses, the patients and their children. I knew they loved me and cared for me. Now I understand there is no difference between race, nationality or religion if we have love and serve each other.

Daphne ‘Pee Wee’ recovered and returned to teach in the camp. Last October Daphne was granted a visa to visit her younger son, his wife and four children who had been granted refugee status in theUSA five years previously. She was able to travel with her first son and his wife and children who were still in Thailand. It was the first time they had been together as a family for five years. ‘God willed it,’ Daphne said with obvious happiness and gratitude.

****

Sister Mary Robert Perrillat is an Ursuline Sister currently based in Ratchaburi , Thailand . She was born in Sta Rosa , California , USA , in 1923. She volunteered for mission in China . Assigned toSwatow in 1947 she did catechetical work and taught English. She experienced two years of house arrest before being forced to leave in 1951 because of the Communist Revolution in China . From there she went to Bangkok , Thailand where she taught religion and singing, in Thai, and English in Mater Dei School for fourteen years. From 1958 till 1967 she taught in the Ursuline Sisters’ ReginaCoeli School for hilltribe children in Chiang Mai , Thailand . For the last 30 years Sr Mary Robert has been working with poor children and families, almost all of whom are Buddhists.

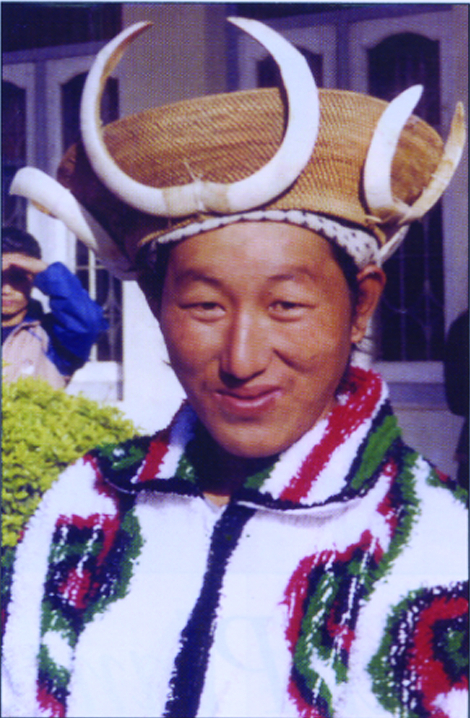

A Kachin from northern Myanmar

She met Daphne shortly after the refugee camps opened along the Thai-Myanmar border near Ratchaburi in 1997. Thousands of Karenni refugees fled to the border at that time because they were literally driven out of their home and lands at gunpoint when the Unocal oil pipeline was being installed there. Since then she has become a ‘Mother of the Karenni’ and a great friend of Daphne. Both have a deep love of children and compassion for the oppressed. Both have a fierce commitment to justice, deep faith, and patience that keeps them active in serving the many needs of refugee children and their families through these past eight years.

Sr Mary Robert works with the Diocese of Ratchaburi’s ‘Border Ministries’ program, which provides medical and emergency health services to the refugees in the camps. She also works with undocumented Karenni people who have come to the Thai villages in search of work – and to escape the fighting that threatens their lives even inside the refugee camps.

Although the great majority of the Karenni are Baptist, this is no barrier to providing services or fostering relationships. Medical missions are coordinated by a joint group which includes a Catholic priest and local leaders. The site is often a Baptist, Catholic or other denomination’s grounds. Catholic Sisters and lay volunteers usually accompany the monthly clinics.

Sister’s keeps her cellphone close by, in case there is an emergency call. She is ever ready to get into her pick-up truck and bring someone to hospital or to supply whatever emergency help is needed. And who can say how much she has helped Daphne provide needed educational tools for the children?

When Daphne was leaving for the USA and met Sr Mary Robert to say goodbye, they shed no tears. The living faith both have in ‘whatever God wants’ and the happy expectation of Daphne’s reunion with her family bonded them. Truly, soul-sisters – their lives continually enriched by the faith and practices of the Baptists, Catholics, Buddhists and animists among whom they have lived and worked throughout their more than 80 years of life.