May-June 2006

Father Joeker

By Fr Joseph Panabang SVD

CEMETERY

One time I brought my cousins, Henry and Benita, to our cemetery at Christ the King Seminary inQuezon City. I told them, ‘Today we’re going to where I will be one day. When that day comes, you must come and visit. It doesn’t matter which of the empty graves I’ll be in. I’ll still listen to you from the grave.’ I think I scared my cousins because they asked to leave right away.

BAREFOOTED

While visiting the Missionaries of Charity in Tayuman, Manila, where my niece and cousin are novices, I was wearing slippers. But when I entered the building I saw them walking barefooted. ‘These people are always one step ahead,’ I muttered to myself.

COMPUTER

I placed our newly bought gadget in the office. Some of the catechists from the village was looking at it curiously. I was amused to see one of them proudly telling his companions what the unfamiliar gadget was. ‘This is a computer!’

THE OFFERTORY

I celebrated Mass in Sabie, one of the villages in my parish in Ghana . Surprisingly there were many gifts at the offertory. ‘What’s seldom is wonderful.’ My altar boys were more surprised than I was so I told them, ‘These are the fruits of the Holy Spirit.'

HERE I AM…I WILL GO, LORD…TO NORWAY!

By Sr Cresencia G. Lagunsad CB

Sister Cris, from Kidapawan, Mindanao, has been a member of the general board of the Sisters of Charity of St Charles Borromeo, www.cbsisters.org , since 1999 and on 5 August 2005 was elected to a six-year term as Vice General Superior.

(L-R) Srs Melanie, Cresencia, Rosarie and Lisbeth - members of the General Board - one Filipino and three Indonesians

January, in the middle of wintertime, I found myself shivering in the Norwegian cold. Worse still, I had just come from a sunny December in East Africa. Some people questioned my common sense about this schedule of extremes! I know what they meant but my heart had its own reasons.

My heart brought me to Norway during this unpleasant time of the year. On 6 and 8 January we were celebrating the 25th anniversary of the religious profession of Sr Agnes Ofelia Simbillo. Being another European-based member of the Sisters of St Charles Borromeo – I’m in the Netherlands – I was privileged to be present at Sister Agnes’ two Silver Jubilee celebrations.

Sister Agnes is from San Luis, Pampanga. Se studied and worked in Manila, where she also met and later joined the CB Sisters in November 1977. After her first profession she was assigned to Bukidnon for several years. Prior to her assignment in Norway, she was a missionary in Indonesia. Now, she’s in her eleventh year in the Catholic Diocese of Oslo.

The celebration on 6 January in Oslo was organized by the Filipino community there. Sister Agnes serves as a pastoral worker in the Filipino Chaplaincy of the Diocese of Oslo. The political and economic stability of Norwegian society is no assurance of a blissful life, especially for those coming from foreign lands. The integration process in a new culture and a totally different climate demands much from one’s physical-mental-psychological-spiritual capacity for healthy survival. In the midst of material abundance and convenience, there are consequences affecting the quality of human interaction.

Being a Filipino herself is a big help in Sister Agnes’ pastoral ministry. Not only does she reach out to the Filipinos all over Norway , but also to others from different countries and faiths. She has to deal with issues related to differences in culture and religion in marriage, domestic violence, juvenile delinquency and even the acclimatization of newcomers. Bishop Emeritus of Oslo Gerhard Schwenzer SS.CC invited the Congregation, through Sister Agnes, to minister to the Filipino community in Oslo and gave his full support, truly a blessing.

At the celebration on 6 January, which began with Mass in St Olav’s Cathedral, I met several missionaries assigned to other parts of Norway . From the Philippines were two Catholic priests and a Dominican Sister. There were also Sisters and a priest from Vietnam.. Definitely, it wasn’t an exclusively Catholic gathering but a fellowship of believers graced by Norwegians of other Christian communities and people from other cultures. Generally though, it was a typical Filipino celebration in terms of food, music and spontaneity!

Two days later the parish of Moss celebrated with Sister Agnes, their way of thanking her and her community for being part of its life and for serving its people, too. Together with three Indonesian CBs, Sisters Pauline, Stefani and Adriani, Sister Agnes also helps in running their parish. The four of them, besides their regular jobs, take turns in some parish ministries. Bishop Schwenzer’s successor, Bishop Bernt Ivar Eidsvig CRSA, a Norwegian – Bishop Schwenzer is German – was the main celebrant at Mass, with Father Piotr Pisarek OMI, the Polish parish priest, concelebrating.

The parish is predominantly Vietnamese-Norwegian, very apparent as families filled the church and the reception hall. They also did most of the preparations, provided most of the choir members and their children delighted everyone with their music and dance later. The presentation of Filipinos from a nearby parish added to the fun. One Norwegian guest commented that she felt she was inSoutheast Asia, surrounded by brown people with ‘chinky’ eyes. And the Asian food prepared by the Vietnamese and Filipino communities was a rare treat! In short, the comfort of familiarity and friendship brought warmth to our hearts on a chilly day.

Sister Agnes’ heart couldn’t contain the affection and joy she experienced on her big day. For her, celebrating her silver jubilee far from home didn’t make any difference at all. She was embraced with so much love by the people she has chosen to be with and serve. In one sense these people have never been her own, aren’t her own and never will be her own. She knew this when she accepted the mission. These people whom she is privileged to serve are God’s own people.

In her thanksgiving sharing, Sister Agnes said that her twenty-five years as a religious could be encapsulated in three words: LOVE, GRACE and FORGIVENESS. In whatever ways, big and small, her experiences of love, grace and forgiveness were now forever etched in her heart. No wonder she’d always have the inner strength and faith to embrace God’s people in her heart even in the far away and cold land of Norway .

And God has marvelous ways in taking care of every one in their choices of serving God’s People anywhere and in varying circumstances. Sister Agnes’ time and place now is in a multicultural Church in Norway. It’s not a bed of roses though, but God is with her, faithful and forever journeying with her. Only a heart that loves knows that!

Congratulations and thank you, Sister Agnes. May your kind increase!

Pedaling To Live

by Fr Oliver McCrossan

More than 3,000 pedicab drivers in Ozamiz City endure grueling work and long hours to support their families. Here are two of their stories. Columban Father Oliver McCrossan came to thePhilippines from Ireland in 1976.

Josefina pedals passengers like these through Ozamiz streets on his three-wheeled pedicap called a sika-sikad

Josefino: Overcoming a Disability

I met Josefino as he stopped to pick up a passenger. He was dripping head to foot from the heavy rain and looked miserable. Josefino is just one of more than 3,000 sikad-sikad drivers in Ozamiz. These three-wheeled pedicabs are the city’s main means of public transportation. Sikad-sikad drivers all come from the poorest barrios of Ozamiz City, and almost all are forced into this work because there just aren’t any other jobs available.

One positive side of this is that Ozamiz has less pollution from traffic fumes and noise than other cities in the Philippines. The sikad-sikads provide jobs and the local industry that manufactures and repairs pedicabs provides work for many others.

Josefino Baylo was born in 1965. His mother told me that when Josefino was very young, a local doctor gave him an overdose of medicine that left him paralyzed. He recovered somewhat but now walks with a limp. He didn’t finish high school and, as the eldest in his family, was forced to leave school and work to support the family. He lived by the seashore, diving for crabs and selling them at the local market.

But this didn’t provide enough income for his family. So in 2002, and in spite of his severe handicap, he decided to drive a sikad-sikad. Josefino and his wife, Helen, have three young children. Helen took in laundry for washing to earn money, but got sick. She says, ‘My back was painful, and I developed a stomach ulcer, so I had to stop.’

Josefino begins his day at 6 each morning and ends at 8pm. He brings students to school and shoppers to the market. An average fare is five pesos and he can carry only two passengers at a time. ‘Because of my disability, I am slower than the other pedicabs so I get fewer fares.’

Josefino doesn’t own his pedicab; he rents it for 60 pesos each day. After paying his rental fee every night, he takes home an average of 70 to 80 pesos. This small amount has to take care of his family’s daily needs - a daily struggle just to survive.

‘When I come home after a day out in the sun and rain, I have pains all over my body,’ Josefino told me.

In spite of his disability, Josefino struggles on bravely to care for his family. His neighbors speak of his courage and hard work. They help as best they can, but most of them are poor as well.

Josefino joined an organization that campaigns for the rights of person with disabilities in Ozamiz. The organization only began a few years ago and is slowly making progress with the support of the Columban Sisters. Josefino applied for a loan of P5,000.00 from the organization to set up a little store in his barrio.

After our visit, Josefino pedaled off into the rain, I have promised to visit him and his family. ‘I want you to visit and say a prayer for the success of my shop,’ he says with excitement.

Ermon: The ‘Bicycle Man’

Ninyo is one of Ermon and Carmen's six children. He cannot hear or speak, but he has graduated from elementary and now attends high school

On my first visit to Ermon’s home, I felt sick from the awful stench coming from the stagnant water of the nearby canal. Like many others here in Ozamiz, his house is built next to a health hazard, ‘In 1989,’ he told me, ‘our house was destroyed by fire, we lost all we had, and were forced to move here by the canal. We don’t notice the smell anymore.’

Ermon Lumanta was born in 1948 in Bohol. ‘Life was tough growing up,’ he said. ‘My father was a heavy gambler, and we were forced to sell our coconut plantation to pay off his gambling debts. My mother could take no more, so she left my father taking with her my brother, sister and me. I was only 12 at the time.’

When Ermon was 15 his cousin took him to Ozamiz where he got a start in a bicycle repair shop. Soon, they were calling him the ‘bicycle man.’ Ermon showed me his old and battered sikad-sikad. ‘I bought this second-hand for P1,000.00 15 years ago and it’s still in working order!’ He has been pushing the pedicab for years around the streets of Ozamiz to supplement his income.

‘It’s a hard life,’ Ermon explains, ‘because we’re out in all kinds of weather everyday, just to earn a little to care for our families.’ Ermon’s average daily income comes to about P100.

In 1973 Ermon married Carmen. The couple has six children: two girls and four boys. In 1985, Ninyo weighed only four pounds at birth. Carmen says, ‘I was worried. He was one-year-old, yet wasn’t speaking. We took him to the doctor who told us that due to a birth defect, he would never be able to hear or speak. It was very difficult for us to accept.’

But good news came to the Lumanta family. Columban Sister Mary McManus from the USA had just started a school for the Deaf in Ozamiz and Ninyo started attending. Ermon remembers the family’s gratitude to Sister Mary and her Community of Hope School.

Ninyo graduated from elementary school and is now attending high school. He is adept at Sign Language and hopes someday to teach. He is now 20, a young man full of confidence.

Both his parents are involved in the activities of the Community of Hope School. Ermon says, ‘Carmen is much better at “signing” than me, because she has taken a course in Sign Language. We have seen how it helps the hearing-impaired and other children with special needs. We are proud to be a part of this work.’

Like his sikad-sikad, Ermon with Carmen and Ninyo, has suffered ‘the storms of life,’ but have never been overcome by them. Like Josefino and Ermon there are over three thousand sikad-sikad drivers in Ozamiz City. They depend on what they can earn each day to take care of their families. They provide a valuable service for the people going about their daily business. Like Josefine, the vast majority of the drivers rent their pedicab on a daily basis. The People's Cooperative Bank in Ozamiz has started a small project to assist the sikad-sikad drivers and their families to own their own vehicle. Hopefully it will lead to a better life for some of them.

Salamat sa Columban Mission

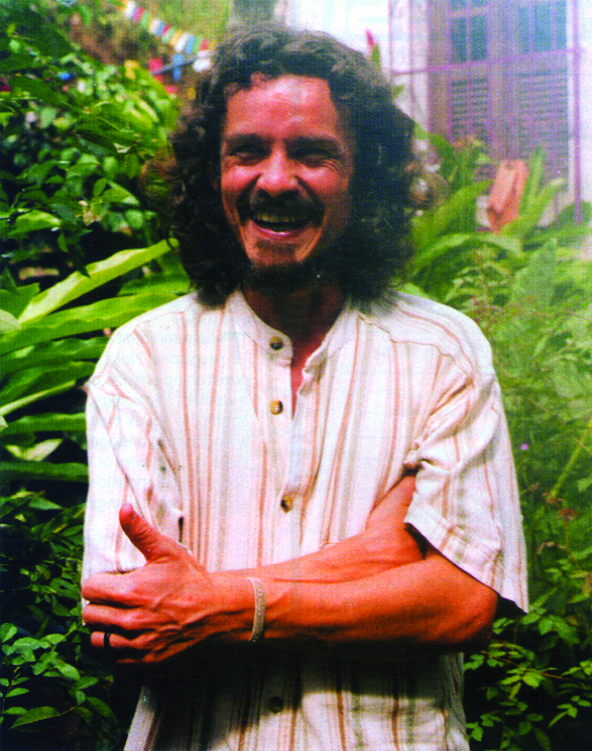

Pilgrim Of The Street People

An Interview With ‘Henrique Of The Trinity’. His Cloth Shoulder Bag Contains All His Worldly Possessions: A Bible, A Crucifix, An Icon Of The Trinity And A Towel.

An Interview With ‘Henrique Of The Trinity’. His Cloth Shoulder Bag Contains All His Worldly Possessions: A Bible, A Crucifix, An Icon Of The Trinity And A Towel.

Q. Can you tell our readers how you arrived at this special vocation in the Church?

A. I was born in France and arrived in Brazil in 1987. I began to live in one of the large, very poor favelas of São Paulo. I spent two years living there, getting to know the situation in Brazil, living in a small wooden shack, the same kind of shack that everybody else lived in all over that area. I had come to Brazil to share in the life of the most marginalized people and to try and lead a life of contemplative prayer in that setting. I did not go to the favela to help resolve the huge problems of the people there, I just wanted to work on a person to person level. I spent two years there and they were happy years, but deep down I somehow felt called to something deeper, a greater simplicity of lifestyle.

I still had a small house of my own, and a small job and I was very much aware of so many poor persons who lived in the parks and alcoves of the great city, who had neither job nor shelter.

So I came to stay with the small group of monks in Taize, Alagoinhas, and I spent six months in a hermitage with them. There it became clear that I was called to be a pilgrim. This life would have two dimensions: as contemplative aspect – I felt called to dedicate myself as a monk, (granted a very peculiar and special kind of monk!) living a monastic vocation as a hermit and as a pilgrim. So, a monastic life, but also a life on the roads, together with those who were most abandoned those who had no homes, those who walked the roads begging alms, those who slept on the sidewalks and alcoves of the cities.

Q. You spent fourteen years as a pilgrim on the roads of Brazil, especially here in the North-East?

A. Yes, I traveled much in the North-East, especially in the sertão (the scrub semi-desert) areas, because that was the area where the people suffered most. It is very sparsely populated so that sometimes one can walk for 30-40 kilometers without encountering a single house. These immense dry arid areas were the places where I traveled most. When I would arrive in the capital cities like Salvador, Recife, Fortaleza, João Pessoa, I would live with the street people and stay there for two or three months. So for the first eleven years it was a life on the roads or on the city streets. I spent long stretches of time in solitude on the roads, four, five, six months at a time – I even went to Peru and all over Amazonia. That and living with the street people, the drug addicts, prostitutes, alcoholics – those who suffered so much violence in the cities, people who had lost everything.

And every so often I would stop for a period at a hermitage. It is extraordinary how a pilgrim will meet up with hermits: I found them in Peru, in Bolivia and even in the sertão.

Q. I loved your book, with its stories of people you met on the roads and on the city streets. Did you ever feel afraid when you were alone on the roads, or perhaps more so when you were sleeping on the city streets?

A. Yes. The street people themselves have many sayings about this: ‘One who sleeps on the streets lies on cardboard and fear is his blanket’. I remember another man who said to me, ‘I’m so afraid to sleep on the streets that I can only do so when I’m drunk, without drinking I can’t sleep.’ So, for street people fear is an integral part of sleeping rough. The more you sleep on the streets the more fearful you become. Many times I have been attacked, many times I woke up at four in the morning having a bucket of cold water poured over me; or being attacked with sticks; even once I remember a group of us sleeping at the entrance of a church, the priest thought we were dirtying the place and he had someone throw disinfectant over us. So the more you experienced these things the greater your fear of sleeping on the streets. In the city of Salvador alone I was taken three times by the night militia, by armed men in unmarked cars without number plates. Once they dropped me nearby, but the other times they dropped us at a distance from the city and really we never knew if we were on ‘a journey with no return’. There were instances of everybody being shot in such ‘street cleanings’ so they caused terrible anguish and we would be warned never to return to Salvador. Of course we would be back in Salvador the following day. But really fear is part of living on the streets. Fear is no sin. It’s part of our make-up and God does not take it away. What God does is to give me peace of heart to live with this fear, so that even though I am afraid, I don’t lose interior peace.

Q. I get the impression from your book that the people whom you encountered on the streets and on the roads were also the greatest stimulus for your prayer life.

A. Encounters with other people certainly nourish one’s prayer life: I can truly say I meet God in these encounters; they are an authentic experience of God. But in order that such encounters should happen one needs to be a person of prayer. We are more open to such encounters when we allow God time to prepare us for them, so that when the moment comes we have that interior liberty to allow others to come into our life. If we are moving too fast, if we are on our guard with people, these encounters just won’t happen.

Sometimes one just is not welcomed. I remember once I spent a whole week sleeping in the open in the sertão without being welcomed. But then I would say to myself, ok, if I am not welcomed by anyone today, it must be because God is preparing me for a very special meeting. And sometimes it happened. On such occasion, I think, God immerses you in solitude, deep in the mystery of Himself, in order that you will be sufficiently empty of self to make space for the other through the open doors of your being. And so I got into the habit of living such days of solitude as an inner preparation, a kind of self-emptying, so that at the moment of meeting I could allow the other to enter freely into our encounter.

Q. It seems that the voice of the Spirit led you in a different direction in the year 2000?

A. Yes, there were various factors involved. Right from the beginning I was often asked why I would not set up some kind of shelter for street people. And I would just say, ‘No, a pilgrim does not do that.’ But then over the past five years there were more and more requests from the official Church, for days of recollection, retreats, spiritual direction, people who wanted to journey with me, later groups who wanted to make pilgrimages, in threes or fours initially and then fifteen persons. I tried to respond as generously as I could, but at the same time there was an inner resistance in me. I found myself asking whether this was leading me away from my original vocation of being a pilgrim. I even thought of leaving Brazil and Latin America altogether and going to Africa or Asia and beginning all over again. Because, by this time, I was well known here in the North-East. It was a difficult time for me.

After a ten-day retreat it became clear that I should respond joyfully to the requests of the Church. I had my own desires, but there were also these frequent invitations of the Church which also brought me joy. So I made my decision and something changed: the internal tension disappeared and in its place I felt great joy. And it was about that time that we received a new archbishop here in São Salvador de Bahia, Dom Geraldo Majella Agnelo, now a cardinal. When he had been here about five months there was a front-page article on the local newspaper, A Tarde, about the street people in Salvador, saying that nobody was doing anything about them, and asking explicitly, ‘What is the Catholic Church doing about them?’ In fact there was very little being done, but someone spoke to Dom Geraldo about what I had been trying to do. He invited me to come and see him and asked me many questions about the street people. Then he said, ‘I’d like you to consider if it may not be time for you to do something along with these people.’ I had my usual answer ready, but he said, ‘Why don’t you set up a little community of street people to welcome the others?’

I was so struck by his question. Two years previously I had indeed thought of a small community of street people, but I had never spoken of it to anyone. So he was really revealing my own heart to me. We began to look for a big shed, or something in the inner city, where the street people would be welcome to come at night: during the day they could be on the streets as usual. For more than a year I searched. Then in March 2000, in preparing for a little pilgrimage through the city I tried to enter the old church of the Holy Trinity to pray. I found that the church was locked and had last been in use ten years previously. This immense church was vacant and unused. So I went to talk to Dom Geraldo and he immediately agreed to our using it. It was the church of the Holy Trinity, I call myself a pilgrim of the Holy Trinity, and it was the year 2000 – the year of the Holy Trinity. First of all it was to be a place of worship, like any other church; but also, from the beginning Dom Geraldo gave it to us as a dwelling place for the street people. So we spent six months cleaning it up and making the necessary adaptations. We did all the work ourselves. There was no running water, no toilets, no electricity, but little by little we got it in shape and began to invite the street people.

We are a small, fragile community, a couple of volunteers and a few street people, and we have no pretensions. But the important thing is that the street people sleep here and the door is never locked. They say, ‘I sleep in the church’ and they say, ‘The Holy Trinity has welcomed me.’ And when they say that, on one level I know they mean that this stone building which is called the Church of the Holy Trinity welcomed them, but on another level they mean that the Church, the Body of Christ, welcomed them and that they are part of that body.

Q. So, you have a small community who live here, and you have a group of street people who come to sleep here, every night?

A. Yes there are two groups. There is a small fraternity: a few people who choose to live here in the Church of the Holy Trinity, we live very simply, we gather unwanted vegetables at the nearby market, we sleep on cardboard with the street people at night in the church. At the present time there are two women and about six men – the number goes up and down a little in our fraternity. We live a life of prayer and contemplation at the service of the street people. Then there is a larger group of street people whom we welcome every night, from about eighteen to twenty-five persons. After they’ve been coming for about three weeks, if they want to identify more closely with the community then they do and we would have fourteen or fifteen in that community. We have meetings together, a Mass once a week, a prayer service each evening and occasional retreats. It gives them a sense of identity and they say proudly, ‘Yes, I am a member of the community’ and it does give them a real sense of belonging. They participate in community activities and each one has their own chores. They have rights and duties, something they never had on the streets. And then there are a number of others who come here every night but do not as yet belong to the community. The phrase that sums up best what we are about is a phrase that is found often in the New Testament, the first phrase that Peter speaks in the Acts of the Apostle: ‘Get up and walk!’ It is quite striking to note how often Jesus speaks this phrase in the Gospels. And in our shared prayer together here, it became clear to us that this was what Jesus most desires for the street people.

The task is to uncover the beauty of each human being that is often buried under years of abuse and neglect. It doesn’t matter what has been their history, here each one is ‘brother’ or ‘sister’ and is greeted and treated as such. We don’t have to make them beautiful, they are beautiful already as human beings, it’s just a question of awakening again that which has been traumatized. To trust others is the fundamental first step, as it was on the streets: I would always leave my shoulder bag with the other street persons and they left theirs with me. I trusted them and they never betrayed that trust. In twelve years of sleeping rough I was never robbed by the street people. The police robbed me, yes, never the street people. And it’s the same here: when you trust somebody you awaken his capacity to be trusted: they say ‘I am considered worthy of trust so I will show that I am worthy.’

Salamat sa Far East

Sharing The Flores De Mayo In The USA

By Armando Machado

The author, who writes for The Catholic Northwest Progress, www.seattlearch.org/progress, is originally from Panama. Raised in New York, he has been in western Washington State since 1987.

Church of the Assumption

Bellingham, WA — Pilar Lim was happy to share her traditional Filipino celebration honoring Blessed Mother Mary with members of other cultures within the Assumption Parish community.

The Zagalas

Unity with other cultures

‘It is the tradition in our country — and here we have unity with other cultures,’ Pilar said Sunday morning shortly before the start of the parish's annual Flores de Mayo celebration, which drew several hundred people.

A longtime Assumption parishioner, Pilar works as a volunteer at the event each year. She said she is thankful for the parish's support, and for the loving leadership of head organizer Filipino-born Cris Finnigan — a fellow longtime parishioner.

Different colors, one faith

Also at the celebration was Jose Cruz, 36, who helped carry a statue of Our Lady of Guadalupe during a brief procession that preceded a regularly scheduled Spanish Mass. That statue was part of the event to acknowledge the Hispanic community, with a statue of Our Lady of Lourdes for the Filipino community, and of Our Lady of La Vang for the Vietnamese community.

‘This is a very good thing — that the Filipino community here has invited us all to celebrate their tradition,’ said the Mexican-born Cruz. ‘The Catholic traditions in Mexico and the Philippines are very similar. We have a lot in common.’

He said it was a pleasure for him to volunteer for the event and to learn more about the ways Filipinos celebrate their Catholic faith traditions. And like Pilar Lim, he noted Cris Finnigan's hard work as lead organizer of Flores de Mayo and other annual Filipino faith-based events at Assumption. Cruz's 15-year-old stepdaughter, Brittany Self, was part of the procession, portraying one of the several reynas (queens).

Devotion to Our Lady

Spanish missionaries introduced the Flores de Mayo during their country’s occupation of thePhilippines, according to written material prepared by Cris Finnigan and other organizers. In thePhilippines, it’s a month-long celebration every May in honor of the Virgin Mary. Traditionally, Filipinos pray during the celebration for a variety of intentions — for rain because of the hot and dry weather, for a good harvest, and for a good marriage, the written material states.

Following tradition, sagalas (young girls dressed in white) bring flowers, pray the rosary and sing hymns to a statue of Mary, usually Our Lady of Lourdes. At month's end, after the sun has set, the statue is mounted on a carosa (carriage) bedecked with flowers and paraded around the city with a band, with procession participants carrying lighted candles and the young girls carrying baskets of flowers.

Multicultural banquet

Flores de Mayo is a month-long celebration in the Philippines, every May in honor of the Blessed Mother. Children bring flowers, say the rosary and sing hymns to the Blessed Mother.

Flores de Mayo is a month-long celebration in the Philippines, every May in honor of the Blessed Mother. Children bring flowers, say the rosary and sing hymns to the Blessed Mother.

After Sunday's 12:30pm Mass, the celebration featured a multicultural potluck in the AssumptionSchool gym, as well as performances that included Filipino, Mexican, Vietnamese, Irish and Scottish music and dancing. Father John Francis Bentley was celebrant of the Spanish Mass, which had aFlores de Mayo theme and was tinged with Tagalog, the main Filipino language, and Vietnamese. The event began several years ago at Sacred Heart Parish in Bellingham, but was moved to Assumption Parish in 2002 — making Sunday's gathering the third annual Flores de Mayo celebration at Assumption.

‘We got such a positive response from everyone — and there was plenty of food,’ Cris Finnigan said. ‘It's beautiful when you're able to draw from other communities and celebrate our diversity, all in the name of Christ and the Virgin Mary.’

http://www.seattlearch.org/FormationAndEducation/Progress/052004/20040527_FloresdeMayo.htm

Soul-Sisters – The Myanmar Connection

Two vibrant women, one aged 85 and the other 84 share stories of how the children ofMyanmar (Burma) bonded them. Burma was renamed ‘Myanmar’ in 1989.

A Buddhist temple in Yangon, Myanmar's capital city. Eighty-nine percent of people in Myanmar are Buddhist.

Daphne Tun Baw (85) tells her story.

I was born in Thaton, Mon Division, Burma in 1921, and my sister, Violet, less than two years later. My mother died when I was five and my father when I was nine. When he died, our grandparents and two aunties and an uncle from my mother’s side looked after us. We both started kindergarten when I was nine and my sister was seven. When I finished Grade Seven I was already 17. I trained as a teacher for one year and volunteered to teach children in a remote village for a year. I then transferred to the Paan (Baptist) mission school. I was 21 when the Japanese bombed Rangoon and World War II started for us.

All from the cities evacuated to the hills. We teachers continued to do mission work - Sunday School from nursery to the elders, choir and Bible recitation. Every month we went to different villages to have Christian Endeavor and Women’s Meetings. One headman led 15 villages, twelve Christian and three Buddhist. We had no money but didn’t feel hunger. The people gave us food because we taught their children.

When the war ended four years later, I returned to my birthplace and taught at the A.B.M. Karen High School from 1945-48. When Burma became independent from Britain in 1948 the Karen Revolution started, for recognition of the rights of the Karen Ethnic People. Most of the young Karenni men who had been in the Burmese Army, Navy and Air Force joined the revolution. There I met a young wireless operator. We promised to marry when the revolution was over.

I followed my auntie and set up a school in Kyun Wine Village. We had no salary but were happy to help our poor Karen people. They were Buddhists and animists. They didn’t know Jesus. They worshipped their ancestors, the god of trees, the god of forests, of mountains. From 1949 to 1953 I never saw my boyfriend. He was able to send a message to me by wireless only once each year on my birthday. In May 1954 Daniel came to my village with a pastor and a wedding ring. I was busy with teaching and didn’t want to marry, but my auntie agreed to his request because he was a decent man from a Christian family, and also faithful and honest to his promises. We married that month.

After a week he went to a village where his father had a farm and hired men to clear the land to build a house so I could teach there and he could farm. After just one hour of work he vomited blood. He had tuberculosis and needed hospital treatment. It was dangerous for him to go to Rangoonbecause he would be arrested there. He was cared for in the Moulmein Mission Hospital, but had to wait a month for a vacancy. I wanted to be with him but the Karen leaders didn’t want me to leave the school. After discussing it for two weeks, they finally agreed. ‘She worked for five years without salary. As a gift we should give her leave, whether she comes back or not.’ They arranged for two elephants, one for me and the other for the woman guide. My husband’s care cost 150 kyats per month for everything, including food and medicine. Each of his brothers and sisters gave 30 kyats per month. Since I had no salary, I wasn’t asked to contribute – but I wanted to work so I could help. Besides, I wasn’t used to not being busy.

I got a job as a clerk in the Customs Department in Rangoon – offering more than three times the ordinary salary. But my sister-in-law came from Syriam and asked me to teach in St. George Diocesan High School. Since I wanted to teach and was not interested in just earning money, I chose to teach there, and was able to help pay for my husband’s treatment. He was hospitalized for two years and came back to me in 1956. Our first son was born in 1957. Then from 1959 to 1962 he studied in theBible College and got a certificate. Our second son was born in 1960.

From 1963 to 1974 he was invited by Dr Gordon Seagrave, a medical doctor and surgeon from theUSA and a Baptist Missionary in Namkhan, Northern Shan State, to be pastor in the mission. While there, I taught in the high school, and my husband was ordained in 1973.

During those ten years he worked hard. His tuberculosis was cured, but he developed diabetes and high blood pressure. In April 1974 he went to Meiktila for a meeting of the Upper Burma Karen Association, and got very sick on the way back. He went to a monks’ hospital in Pyinmana where the nurses had been his church members, trained by Dr Seagrave. The nurses wanted to send a message to me, but he didn’t agree; it was a two day journey by train for me to come. He died the day I received the message. When I reached Pyinmana the supervisor opened the grave to show me his body. He seemed to be sleeping. He was 51 years old. The doctor apologized, but I told him, ‘It’s not your fault. It is God’s will.’

My two sons, then 14 and 17, went to Rangoon to study. The elder joined the revolutionary army after he graduated from Grade Ten. He was 19. My second son joined the revolutionary army in 1980 when he was 20, after he finished his studies.

I officially retired from teaching in 1983, but continued for three more years. My younger son came to ask me to teach in the Karen camp to help the children. ‘You helped the Burmese Government for 40 years. Now it’s time to help the Karens,’ he said. So in 1985 I took a plane to Tavoy, rode by car for a day, walked two more days across the mountains, then rode another whole day by boat to reach the Karen camp at Methame.

I started teaching in high school right away, but got sick with malaria the next month. The camp was in a mountain jungle. I worked with the ‘revolution children’ from 1985 to 1997. In 1997 the Burmese Army occupied the area and destroyed our camp and villages. We had to flee to the Thai border, to a village called Pu Mong.

A Thai military commander from the 9th Division came to the village with some soldiers informing us that all of us had to return. Our Karen elders and church leaders told him, ‘We can’t go back. The Burmese soldiers will kill us.’ The commander said, ‘They promised they won’t kill you.’ But our leaders said, ‘Don’t believe them. They say one thing, but act differently!’ The commander got angry and said there was no place for us to stay, unless we wanted to stay in the sea.

When I saw how angry he got, I felt I needed to speak. I looked at the commander and told him without an interpreter, in English: ‘Colonel, I am very happy to go back to my land, but I can’t go back now. It is war time and nobody can protect us. We never believe the Burmese. They say one thing, but they never do as they say. We fought the Burmese until now. Our forefathers had to fight all the time to defend our lives and basic rights. As we consider our future, we need to escape and stay in a neighboring country for a while. We considered staying in India, China, Indo-China and Laos but we can’t. Their religion and culture are very different. But Thailand is not very different. The religion may be different because Thais are Buddhist (the Karen are Christian), but the Thai people obey Buddha who taught them to be like Christ. Buddha taught them to obey the Lord, to love their neighbors, to help the poor, to help those who need your help, to feed those who are hungry – the same as Christ taught us. That’s why we have come here . . .’

He became quiet, then replied, ‘You can stay as long as you wish. You can stay until the war is ended.’

Then I added, ‘I want to open a school . . . it’s not fair to let the children be sad and unhappy.’

‘All right,’ he said. “You can open a school and teach what you think is good.’ So I went to a store and took the empty cardboard boxes to use as blackboards. I made stands with bamboo and used these as desks. I used plastic for roofing and as mats to sit on. Someone from the United Nations visited. A few days later, ten teachers from Bangkok came and interviewed me about the time I came fromBurma and chose to become a refugee so I could set up the school. They were amazed at what we were able to do with almost no materials.

After that we moved to Tham Hin Refugee Camp where the NGOs and COERR (Church Organizations for Emergency Relief for Refugees) provided what we needed for the school.

In February 2000 I got very sick and was brought to a Thai hospital for surgery. Because I was so weak, they had to give me intravenous fluids. My Thai doctor visited me every day after duty and would bring me milk and eggs from his home. A new doctor substituted for him on Sunday and asked me, ‘Pee Wee,’ (my nickname, because I am so small), are you a Christian? I saw copies of the Guide Post, Daily Bread and Home Chat by your bed.’ When I told him I was a Christian, he said that on Christmas Day the Pastor told him he could pray for anything he wished. So he and his companions prayed for me. I had successful surgery.

While there, the patients learned I could speak English, but not Thai. They sent their children to me, and I would teach them for ten or fifteen minutes at a time. I became friends with the doctors, the nurses, the patients and their children. I knew they loved me and cared for me. Now I understand there is no difference between race, nationality or religion if we have love and serve each other.

Daphne ‘Pee Wee’ recovered and returned to teach in the camp. Last October Daphne was granted a visa to visit her younger son, his wife and four children who had been granted refugee status in theUSA five years previously. She was able to travel with her first son and his wife and children who were still in Thailand. It was the first time they had been together as a family for five years. ‘God willed it,’ Daphne said with obvious happiness and gratitude.

****

Sister Mary Robert Perrillat is an Ursuline Sister currently based in Ratchaburi , Thailand . She was born in Sta Rosa , California , USA , in 1923. She volunteered for mission in China . Assigned toSwatow in 1947 she did catechetical work and taught English. She experienced two years of house arrest before being forced to leave in 1951 because of the Communist Revolution in China . From there she went to Bangkok , Thailand where she taught religion and singing, in Thai, and English in Mater Dei School for fourteen years. From 1958 till 1967 she taught in the Ursuline Sisters’ ReginaCoeli School for hilltribe children in Chiang Mai , Thailand . For the last 30 years Sr Mary Robert has been working with poor children and families, almost all of whom are Buddhists.

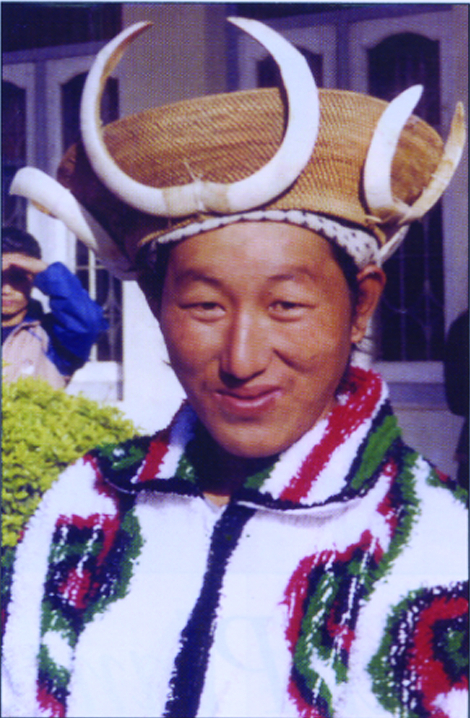

A Kachin from northern Myanmar

She met Daphne shortly after the refugee camps opened along the Thai-Myanmar border near Ratchaburi in 1997. Thousands of Karenni refugees fled to the border at that time because they were literally driven out of their home and lands at gunpoint when the Unocal oil pipeline was being installed there. Since then she has become a ‘Mother of the Karenni’ and a great friend of Daphne. Both have a deep love of children and compassion for the oppressed. Both have a fierce commitment to justice, deep faith, and patience that keeps them active in serving the many needs of refugee children and their families through these past eight years.

Sr Mary Robert works with the Diocese of Ratchaburi’s ‘Border Ministries’ program, which provides medical and emergency health services to the refugees in the camps. She also works with undocumented Karenni people who have come to the Thai villages in search of work – and to escape the fighting that threatens their lives even inside the refugee camps.

Although the great majority of the Karenni are Baptist, this is no barrier to providing services or fostering relationships. Medical missions are coordinated by a joint group which includes a Catholic priest and local leaders. The site is often a Baptist, Catholic or other denomination’s grounds. Catholic Sisters and lay volunteers usually accompany the monthly clinics.

Sister’s keeps her cellphone close by, in case there is an emergency call. She is ever ready to get into her pick-up truck and bring someone to hospital or to supply whatever emergency help is needed. And who can say how much she has helped Daphne provide needed educational tools for the children?

When Daphne was leaving for the USA and met Sr Mary Robert to say goodbye, they shed no tears. The living faith both have in ‘whatever God wants’ and the happy expectation of Daphne’s reunion with her family bonded them. Truly, soul-sisters – their lives continually enriched by the faith and practices of the Baptists, Catholics, Buddhists and animists among whom they have lived and worked throughout their more than 80 years of life.

The Bayanihan Services

By Sister Grace Dorothy Lim MM

Early one morning, I received a call. ‘Sister, please, help us with the Immigration.’ Someone had received notice of voluntary deportation. At 8 o’clock I drove to their house. It was a one-room structure, an extension of a bigger house.

Sister Grace Dorothy Lim MM

One phone call

The caller was waiting for me. The house was dark but I got in to make sure we had all the documents needed for the Immigration Office. The room had only one small bulb, maybe 20 watts. While my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I heard a soft cry. I asked who was sleeping this late. The mother said, ‘The children are all sick with fever and colds.’ This was flu season. I asked if they’d gone to the doctor. She said they had no medical insurance, so she only gave them Tylenol. I told her to get all three children dressed to go with me to the doctor. The woman was, of course, more concerned over Immigration than the illness of the children.

When the children were ready, and we were about to leave the room, I heard another groan from another corner of the room. So I turned around, peered and asked who was there. ‘My mother has a swollen face from a toothache.’ No dental insurance either. So, I told the grandmother to get dressed and go with us. My small Volkswagen was full of patients.

Deprived of medical help

I asked my doctor to look after the sick children and informed the nurse that they had no medical insurance. ‘Please, take care of them and bill the Maryknoll Sisters. I’ll be back after we see a dentist,’ I said as off I went.

Grandmother and I went to the dentist. I wasn’t sure they’d do anything because her face was so swollen. I told the whole story of my discovery to my dentist. He was very kind. He treated her, gave some pills and told us that she should return when the swelling went down. I told him the same thing, ‘Please, bill the Maryknoll Sisters. She has no medical/dental insurance.’ The doctor simply smiled.

Being part of the solution

By the time we got back to the medical building for the children, they were already treated and were waiting for us. I went in and thanked the doctor who told me to give the children plenty of liquid and to get back in two days.

From this experience, I wondered how many more sick people weren’t getting any medical help just because they had no medical or dental insurance. I knew of the Phil-Am Medical Association of Hawaii. I found out that in a week’s time, they’d be holding their annual convention. I managed to contact the president of the association and asked if I could be given a few minutes to address the convention. He was most gracious and invited me to attend. Since I had no ticket for the dinner, he asked me to be his guest.

Plead for support

I prayed for an openness of heart of the doctors and asked God to put the right words in my mouth. When I was introduced as a special guest, the only ones who knew me there were my own medical and dental doctors.

I introduced myself as a Filipino Maryknoll Sister assigned to Hawaii to serve the Filipinos. I told them I was giving all that I knew how to. I also believed that I wasn’t the only Filipino gifted by God with talents, but I knew I was giving all I had and could for our people. But there were many things I couldn’t do, that I wasn’t trained to do.

Holy Spirit working

I then shared my experience with that call to help with Immigration, which led me to medical and dental trips. I wondered if they ever thought of the possibility of many, many Filipinos without proper medical and dental care simply because they couldn’t afford medical coverage. My story moved a good number of them. I prayed to the Holy Spirit to touch their hearts. I then challenged them to work with me for a more holistic service to our people.

Two days later, I got a call from the president asking me to have lunch with him. Jokingly, I said, ‘Does your wife know about this?’ This lunch meeting was actually the planning stage of the project. He said the doctors were willing to give their time and services if I could give them a place to work. Well, I wasn’t in real estate but I promised to do something about getting a space.

God’s providence

I went to the Bishop and asked for the use of the room attached to our building, the chapel area of the old convent, for the use of the doctors. While the Bishop was excited at the prospect of a medical clinic without immigrant services, he had to consult and get the permission of the Pastor of the Co-Cathedral. When all permissions were given, and after an hour’s ‘lecture’ from the pastor that day I went to get the keys. We had the building surveyed by our Filipino Carpenters of Hawaii. Repairs started and our Bayanihan building was ready for use in a week’s time. Lighting and plumbing were taken care of by Filipino electricians and plumbers who were patients of the doctors. When all that was done, the doctors’ wives came to clean the room, polish the floors, put curtains in the examining rooms and flower pots around. In two days, we had the building blessed and had an open house. We had the Bayanihan Health Services running, and we also added legal services with our volunteer lawyers.

Life in the old building

The old condemned convent was teeming with service activities. During the day we had socio-economic, educational ministries and in the evening the medical, dental and legal services were busy.

Palama Settlement

Our immigration services are now under Catholic Charities, and the Bayanihan Clinics are housed at the Palama Settlement. It is the base clinic of the Aloha Medical Mission (http://www.alohamedicalmission.org/), now serving many poor countries in Asia and the Pacific and with doctors and nurses from several ethnic backgrounds.

Walking With Overseas Workers

By Beth Sabado

The author is a Columban lay missionary working at the Hope Workers’ Center in Chungli City,Taiwan.

Working in the migrant ministry, I get used to all the ‘hellos’and‘goodbyes’ from migrant workers coming and going. Before leaving, some share their excitement to be home with their family, their anticipation of playing with their children and handing over their mga pasalubong. Others share their worries and fears, what to do when their little savings will all be spent, how to relate to their children, concerned if the kids would still recognize them, how to deal with an unfaithful spouse, how to handle a sick family member. Others promise not to return. But after a while they’re back again.

(R-L) Beth and Fr Peter O’Neill with other social workers

of the Hope Worker’s Center

Different nationalities, Thais, Vietnamese, Indonesians and Filipinos, gather in the center, especially on Sundays. I work with almost 200 Filipino volunteers, each having a different personality, attitudes, intensity of service and commitment and with varied experiences and struggles.

One of the center’s services is the Reintegration Program, designed by the Asian Migrant Center inHong Kong. As a lay missionary, I work in partnership with Columban Father Peter O’ Neill, the director of the center. We facilitate the formation of savings groups. We organize and give seminars for the workers, teaching them the value of saving money to accumulate capital for future investment. In one of the group sessions I facilitated, I asked the workers how they felt about sending their remittances home. Their answers surprised me: ‘I feel obligated . . . I feel abused . . . I feel pressured . . . I feel it’s my responsibility . . . I feel tired, but . . . I feel disappointed because . . . I feel glad, but . . . I feel scared every time I receive a text message from home because I know what it means . . . I just hold “my” money for a couple of hours when I’m heading to the bank, sigh . . . I feel sad that I don’t really own my money . . .’ and so on. As I listened to their sharing, I heard the men’s voices begin to break and saw the women’s eyes become moist. I felt my heart throbbing.

As I journey with the migrant workers, I hope and pray that they will have a strong sense of their worth and that their families truly appreciate their sacrifices.

You may email the author at bethsablm@yahoo.com or write her at St Columban’s, PO Box 328, HSINCHU30099, TAIWAN

Your Turn

A Young Reader Of Misyon Shares With Us A Simple Yet Profound Reflection After Reading And Being Inspired By Our Magazine.

By Sabrina Gloria

Dear Father Seán,

Reading Misyon I’m touched by some of the articles. Because of this I would like to share my insights about a simple gesture which has left a special dent in my heart. I hope you’ll appreciate it.

Every time I travel, like most people, I tend to stare out the window and check out the streets, the other cars, the buildings, the houses and the people. I watch as men and women, the old and the young, go about their business. What really catches my attention are the rugged street children who scurry about almost without care, either playing their lively games or asking for alms. Silently, I ponder on what goes in their heads. Are they thinking about the next game they’re going to play or the next bit of food they could cram into their stomachs in the future? Are they thinking about what goes on in other places or imagining the most impossible and colorful things as I imagined as a child? Do they really think about ‘important’ things like what they would be in the future or how they would help society and not get utterly lost in the gloomy and dark haze of the streets?

Not long ago, I caught a glimpse of two street children happily sharing a piece of bread and a glass of juice. That time, I fondly remembered one of my outreach trips to Pandacan with my schoolmates. We were greeted by smiling faces and some warm hugs from the children. It was their book parade that day and there was a very obvious air of excitement. I took care of two boys who were about seven-years-old. Being as they were, both were vigorous and full of adrenalin. Truthfully, I felt dizzy for a while as I tried to keep up with both as they raced each other and got themselves in to small fights with the other kids. Although I had to repeatedly mend and fix the costumes of those whose ornaments were torn or stripped away by my kids, I really had fun.

After the parade, I got burgers and drinks for my boys which both finished with gusto. There were extra burgers on the food table which I took to them in case they were still hungry. Each got two extra burgers. I waited for them to eat and when they contentedly placed their burgers on their laps without any intention of eating, I asked them what they were saving the burgers for. I was curious because they had this knowing and distant smile on their faces. One whom I affectionately called ‘Daga’ because of his costume was the first to speak. ‘Para po kasi ito sa nanay at kapatid ko. Gusto ko po kasi mabigyan sila ng pasalubong.’ This was his proud reply. The other had the same intention. I was touched. Were these the same children who bullied the tallest of their group just because they wanted to? I never knew these mischievous boys could have such love and devotion for their family as shown by their thoughtfulness. That time I realized that these children do not think only about their own desires or what interests them at the moment. They knew something that some of us only learn during our early teens. They knew how to care by thinking of others and of the happiness of the people close to them: a simple gesture which may seem simple but is magnanimous in its own way.

As I kissed them goodbye, I felt a surge of pride. I knew that even in their condition and environment, they had direction and virtue. That day, I had been a witness to something I hold to be immense in its effortless way.

Sincerely yours,

Sabrina Gloria,

St Scholastica's College, Manila

Your Will Be Done, Lord!

By Reverend Noe H. Pedrajas

The author was ordained deacon on 15 November in preparation for the priesthood. He belongs to the Diocese of Marbel.

During the ordination

to diaconate at Cacayan de Oro

Cathedral, with Bishop Zacharias Jimenez,

auxiliary of Butuan

One Monday while praying the Joyful mysteries, I got stuck in the Annunciation! The Annunciation struck me as an extraordinary mystical experience. I realized that the unfolding of God’s plan of salvation wasn’t fulfilled without the ‘Yes’ of our Blessed Mother Mary. Her ‘Yes’ or ‘Fiat’ didn’t come so easily and spontaneously. It was accompanied by many fears and amazement.

Mary’s astonishing example of giving up self for the sake of God’s will led me to reflect and examine how deep my commitment to God was.

God’s Great Love

Just like our humble Mother Mary, my ten years in formation for the priesthood are marked by moments of grief and feats, of wounding and healing, of torments and predicaments and shouts of joy, from which I’ve moved on despite imperfections. Every time I’m tempted to get stuck in my own selfish world, I’m reminded of God’s tender love and compassion as I respond to His call to the priesthood. There’s no reason for me not to love others, because God’s unconditional love has changed me, no reason for me not to be compassionate, because He has embraced me in spite of my wicked ways.

As I embrace my own struggles, I’m reminded of the struggles of so many others. Selfishness often takes the center stage of everyday living, evil invading the world. Virtues such as compassion, love, sympathy, kindness, empathy, meekness and humility seem nonsensical.

Is there a room for love?

Truly, in a world where so many are preoccupied with getting ahead, even if it means stepping on others, the question is: Will there still be room for unconditional love?

One afternoon in 2000, I went window-shopping in a newly-opened mall in Marbel, South Cotabato. I was walking fast through the entrance when I saw a beggar. Feeling annoyed, I quickened my stride to avoid him. But as I approached the entrance, I noticed that he was staring so badly not at me, but through the window of the mall at the world of food-chains. Though disturbed, I just went inside the mall, as if heaven could be found there.

Gift of conscience

Inside the mall, the sight of that innocent soul of more or less eight years old stayed with me. I felt the stirring of guilt. God wanted me to come closer to him, to listen and talk to him. God was so real that afternoon as if patting my shoulder and emphatically saying, ‘Noe, go to him! Forget yourself!’

As I busied myself inside the mall, the beauty of material wealth had no appeal for me anymore. God was simply irresistible. I strode to the exit where I had seen that boy just a minute before. I looked around but he was nowhere to be seen. At that moment, the world was so desperately sorrowful to me. I pondered on the abundance of God’s grace flowing so deeply and giving me life so that I might share it with others, and yet here I was, busy loving my selfish self!

Human weakness

God’s challenge to us is to be like Him in so many ways. Our life is one of grace. As children of God we live in the world in hope, faith and love, sharing with others whatever grace we receive from Him. Deep within my heart there was this inner longing to do an act of generosity yet my human weakness prevailed.

My humbling experience that afternoon reminded me of my father, who lived a life full of sacrifices for others. He was the friendliest person I’ve ever known. Almost everyone in the barrio seemed to be his friend. He would usually visit a friend, a relative, or just a not-so-close neighbor, if ever they were sick or in difficulties. He would often bring them produce from his small farm. One time whenTatay found out that a distant relative had been sick for almost a week, he found a way to bring our relative to the local hospital. He lent a little money, since our relative had none. I couldn’t help but being touched by my father’s generosity and thoughtfulness beyond compare. My mother at times had difficulty in determining if that was a virtue or not. But for my father, everything we receive from God is a gift and so it is our gratitude to return it to Him through loving generosity towards others, without expecting any return.

Tatay’s good example

The newly ordained deacons with Bishop Zacharias Jimenez

(Reverend Noe - extreme right, back row)

Then towards the end of 1992, Tatay was stricken with an illness that crippled him. News of his ordeal spread all over our locality. Though his friends surely heard the news, only a few visited or helped. But, I admire Tatay for his humble generosity. Though he lost most of his friends when moments of ordeal came, though he lost his money to needy persons, though he lost even his life,Tatay’’s entire life was a dynamic evidence of how to give love unconditionally.

It was grace because it called him to life and because it gave him the only true life.

The permanent joy

Indeed, I’ve discovered what life is all about. It’s all about generously giving one’s life to God and to others - and forgetting oneself in the process. It’s the only way for us to have genuine, permanent joy - loving until it hurts!

¿PERDIDO? LOST? Lost (And Found) Missionaries

By Sr Emma de Guzman ICM

What happens when Filipino missionaries working all over the world come home, either for vacation or for good? Just imagine them in Africa or in any other part of the world, giving their best to the people they are called to love and serve, sharing those people’s lives and dreams and struggles, learning to speak their language. Then after five, fifteen or 30 years they must come home to thePhilippines. They are somehow lost. They experience cultural shock in reverse. The Philippines has changed and is still rapidly changing.

But foremost, the Filipino missionaries have changed, have imbibed the culture of the people they were sent to and have shed a part of their being Filipino. Their families love and welcome them, although some find them ‘weird’ or out of place in some way. They need time for their re-entry and readjustment to the home country. They keep asking questions that are irrelevant for those who’ve never left the Philippines. Their sentences often begin with ‘In Bostwana’ ‘in Argentina’ or ‘in Haiti . . .’

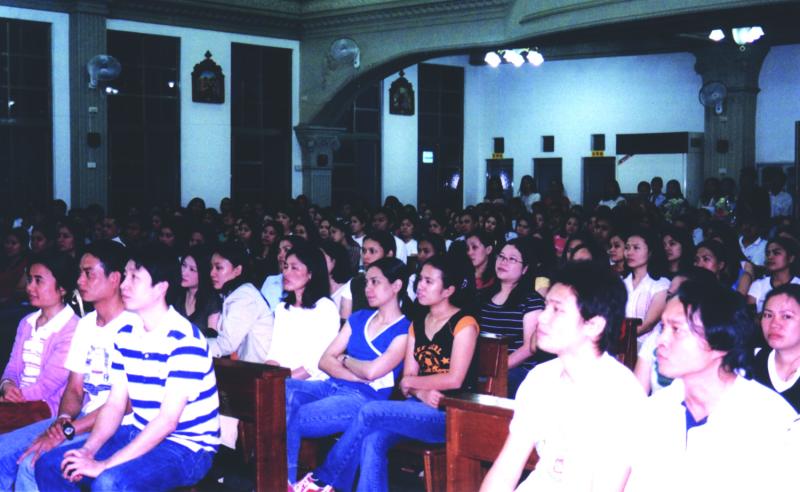

But when they come together for an eight-day renewal and enrichment seminar, they are happy and are transformed from being lost to being found!

This was the joy of living together the 16th BAMEP (Balikbayan Missionaries Enrichment Program) at Holy Spirit Mission Service Center, Tagaytay City, last December 1 to 9. The facilitators were Sr Mary Evelyn SSpS and Fr Dante Venus SVD.

Sixteen participants shared their life on the missions, prayed together, laughed at their funny experiences and listened to the different resource persons. The aim was to help the balikbayanmissionaries have a successful re-entry into the home front while processing their experiences and coming out adjusted, more or less.

The first two days were facilitated by Fr Edward Fugoso SVD and Tessie Nittoreda. Through the Emmaus story in Luke 24, we were led to looking into our own Jerusalem (where Jesus suffered and was crucified) and Emmaus (where the disciples recognized Jesus) encounter with the Lord while in our different mission countries.

The encounter in itself was healing and enjoyable. When you’re with fellow-missionaries and you tell your story – sad, dramatic, tragic or funny – there’s a feeling of compassion only all of you can understand because you’ve all been in the same situation.

Brother Silas, an SVD missionary for 24 years in Botswana, related to the experiences of Sr Victoria Lerin FMM in Bolivia. The war experiences of Fr Joseph Villas SVD in Angola resonated with the struggles of Sr Herminia Aballe ICM in Haiti. Some heartbreaking stories of Sr Maria Paz de la Paz inChad found resonance in the struggles of Fr Herman Patica SMA in Ghana and Fr Renato Ampol SVD in Zimbabwe.

We cried and laughed together as we listened to one another’s adventures.

Fr Ed Fugoso helped us to look into our past to understand our present state of ‘lostness’ and struggles through the Psychogenetics and Gestalt Method. He made us aware of our ‘imprints’ and how to process our experiences by making our own ‘re-imprints’. A reflective ‘flashback’ of our lives and our missionary struggles allowed us to see where the Lord was and where He actually was leading us. The sharing that followed was like listening to our own stories told by somebody else in another mission country. They were our typical missionary stories of joy, pain, life, death and new life from the ashes.

The days with Fr Ed and Tessie Nitorreda were also times of intense prayer, recollection and holy hours as we recognized the loving arms of our Lord Jesus in our moments of darkness and light.

Fr Dict Lagarde MJ clarified and put words into our ‘weirdness’ when he spoke on the Spirituality of Transition. He told us a story about getting lost in Mexico as a newly arrived missionary. He made us all laugh every time he mentioned the question someone who understood his plight in a bus asked him: ‘¿Perdido?’ – ‘lost’ in Spanish.

He helped us to be aware of the degree of our being lost, to name it and own it. Then we could move forward, less ‘lost’ and less ‘weird’ as we readjusted our bearings to the present Filipino culture and situation.

The highlight of the evaluation was gratitude: to the Lord who called and sent us to the foreign missions and who never left us as we did his mission, and for the SVD and SSpS congregations in organizing this life-saving enrichment program.

The Eucharistic celebrations were colored and inspired by the liturgies of the different countries where we worked.

The last night was a cultural evening of dances and songs. Each participant wore the national costume of their mission country and presented a local song or dance complete with mask and local facial designs

We ended the eight-day program with a tour of the Ayala Museum and the final Eucharistic celebration at Christ the King Mission Chapel, followed by a sumptuous lunch before we said goodbye.

Fellow missionaries, as you read this in your mission countries, be brave. Hindi kayo nag-iisa! And don’t fail to undergo BAMEP when you come home to the Philippines!